Floundering Around (Sustainable Seafood #13)

Flounder and Halibut are some of the tastiest, and wierdest, fish in the sea

The biggest fish I ever caught defeated me with pure stubbornness. It refused to come to the surface, shrugged off my attempts to kill it, broke my fishing rod, then untied the knot at the lure. It was a large Pacific halibut, and I was in a kayak with a salmon rod; a ridiculous and uneven match, destined for failure. Halibut are one of the biggest and wierdest fish in the sea, but if caught, would have been one of the best and healthiest fish dinners I could have eaten.

A Fish Story

It was a bright sunny day, unusual weather for fall in Kodiak, Alaska. I was sitting in a double kayak, with my 15-year-old daughter in the front seat, and we were fishing for rockfish in about 50 feet of water near a cliff on the edge of a small island. Rockfish weigh about five pounds, so I was using a salmon fishing rod with 15-pound test line, plenty strong for a rockfish. Jigging the heavy lure up and down, I was waiting for a fish to bite, when I felt the line stop moving. I pulled harder, but it wouldn’t budge. Darn, I thought, I’ve snagged it on a rock or a piece of kelp. But I kept pulling, and slowly, the line started coming up. I still thought it was snagged, but a piece of my mind was also thinking that maybe, just maybe, I’ve got a really big fish on the line. The more I reeled it in, the more I was convinced. This wasn’t just a big fish, it was probably a halibut.

After about 15 minutes of struggling, I began to see the fish about 6 feet below the surface of the water. It was a whopper. It had to be at least four feet in length, and weighed somewhere between 50 and 100 pounds. Holy cow, I thought, how are we going to land this thing? I told my daughter to take my fish knife and stab it in the heart, hoping that we could bleed it out and it wouldn’t fight us. She stabbed at it, but hit only muscle, which only made the fish mad, and caused it to swim quickly back down towards the bottom.

At this point, I should have realized it was a lost cause, that I could not win this battle, and cut the line to release the fish. But no, this was a trophy, and I had to land it. So, I spent another ten minutes slowly coaxing it back towards the surface. When it came up to the boat, I told my daughter to start paddling towards a nearby beach. But that didn’t work at all – it was like trying to tow a barn door from the kayak. Then the fish jerked, and my rod broke in half. The line was then going out from the reel, through the first ferrule, and down directly to the fish, who looked back at me like he was trying to tell me something; “You ain’t gonna win this, Bubba, better let me go”. At that moment I noticed that the weight of the fish was pulling loose the knot on my lure. As I watched in horror, my knot slowly untied itself, and the fish fell free, sinking slowly back to the bottom. If there is a moral to this story it might be “Don’t fish for halibut from a kayak” or maybe “Know when you are whipped”.

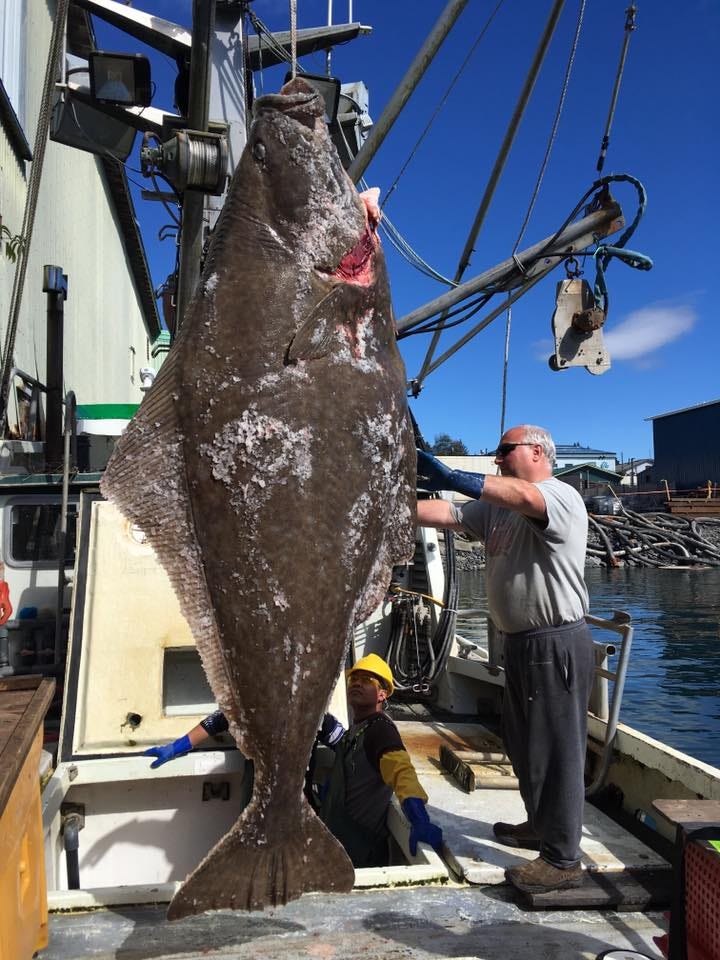

On another fishing trip in Kodiak, my brother-in-law caught a halibut from a 20-foot runabout boat, which turned out to be about 5 feet long and weighed 150 pounds. As we were trying to figure out how to get it into the boat, a man in another boat came over with a pistol and shot it in the head. Only then were we able to bring it aboard, and it still required three of us to lift it over the rail. It’s a good thing our neighbor shot it, because a fish of that size flopping around in a small boat could do some serious damage, breaking someone’s leg or damaging the boat.

Floundering Around

Halibut is a type of flounder, and flounder have to be the strangest fish in the sea. Flat like a pancake, and with both eyes on one side, they look like something you might find drawn in an Egyptian tomb. If a three-year-old drew a fish, it would probably look like a flounder. They are so awkward looking that we have adapted their name for a term, floundering around, that describes an inability to succeed. Yet they are also one of the most delicious fish in the ocean.

Most flounders, also referred to as flatfish, belong in the Family Pleuronectidae. Hundreds of species exist, of which 50-60 species are commercially valuable. All flatfish are laterally compressed, meaning they are narrow from side to side (not top to bottom). When you see a flounder lying on the seafloor, you are actually seeing either its left or right side, not its top (dorsal) side. The most unusual thing about them is that they have both eyes on one side. Whether the eyes are on the left or right side depends on the species, although some species (such as the starry flounder) can be either left- or right-eyed. Unlike most fish, flounders have only one (continuous) dorsal fin and one ventral fin, each composed of many soft rays.

Flounder can spawn multiple times per year. Adult females can produce about 2 million eggs at each spawning. The eggs develop in the water and hatch into planktonic larvae that eat zooplankton. Larvae look like regular fish, with one eye on each side, but as soon as they are competent, they settle to the bottom, and one eye migrates to the other side. Flounder are epi-benthic, meaning they live on the seafloor, where they eat whatever is within reach, including worms, crustaceans, snails, and small fish. Because there are so many species it is hard to generalize, but most flounders live long lives, to 20 or 30 years or more.

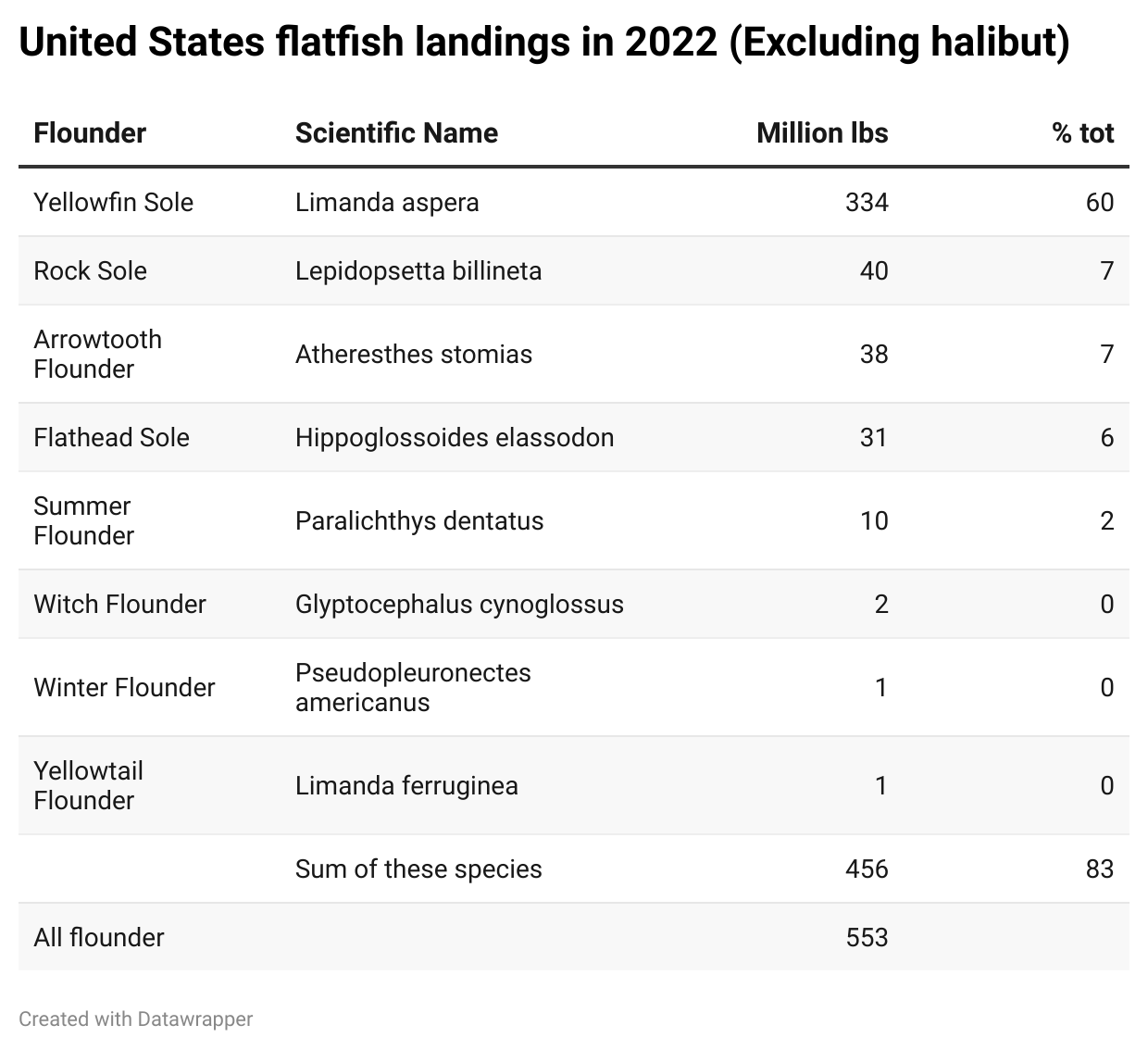

Excluding halibut, four Pacific species comprise 80% of all flounder caught in the United States; five Atlantic species comprise another 4%. Yellowfin sole, of which 334 million pounds are caught in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, comprises 72% of all US flounder catch, and much of that is sent overseas. Rock sole (9%), Arrowtooth Flounder (8%), and Flathead Sole (7%) are the other major species. All four of these are right-eyed flounder. Along the US Atlantic coast, Summer flounder make up another 2% of the catch, and Witch, Winter, and Yellowtail flounder are all <1% of the total flounder catch.

Most flounder are caught by trawl fisheries, which catch many other types of fish, and are managed by NOAA as part of multi-species fisheries. These types of fisheries generally create lots of bycatch, but NOAA has regulations in effect to reduce bycatch and achieve full utilization of the catch. Most flounder populations are well regulated and not overfished. Summer and Winter flounder were previously overfished but are now considered to be recovering.

Flounder are generally sold whole, or as headed and gutted fish. Larger fish, like Arrowtooth flounder, may be cut into filets or steaks. In many coastal communities, whole fried flounder is a signature seafood dish. When cooked, the flesh is light, flaky, and very delicately flavored, so it mixes well with other condiments. Around Chesapeake Bay, flounder stuffed with blue crab is a great delicacy, often called Flounder Imperial.

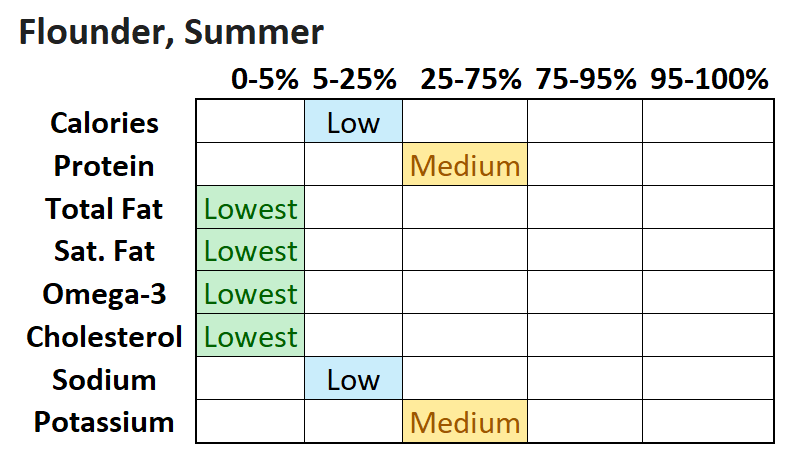

Nutritionally, summer flounder has medium levels of protein and potassium, is low in calories and saturated fat, and has extremely low levels of total fat, omega-3 fatty acids and cholesterol. Since they live in the ocean and are low on the food chain, they have very low levels of pollutants such as mercury or PFAs. Thus, they are extremely safe to eat, and highly nutritious.

A Whale of a Fish

The Pacific Halibut Hippoglossus stenolepis, the kind that broke my fishing rod, is the largest flounder in the world and is high on the list of desired seafoods as well as a primary target for recreational fishing.

Where: Halibut live from California to the Gulf of Alaska, and Bering Sea.

FAQs: Halibut can grow to 8 feet in length and up to 500 lbs in weight and live from 20 to 50 years of age. They mostly eat smaller fish and crustaceans.

Fishery: In the commercial fishery, halibut are caught almost exclusively with on-bottom baited longline gear. Longlines may be thousands of feet long and carry thousands of hooks. The use of large circle hooks prevents smaller fish from taking the hook, thus reducing bycatch, and enables fishers to release small fish with low mortality rates. The fishery is managed using Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs, see below). In 2022, landings were 25 Million pounds, valued at US$137 Million. About 20% of the catch is made by recreational fishermen, or for personal use.

Status and Sustainability: Pacific Halibut stocks range through both US and Canadian waters, so are jointly managed by the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC). Stocks are well managed and are not overfished, so their sustainability is high. Seafood Watch has Certified Pacific Halibut fisheries in the US, Canada, and Russia.

Product: Halibut are usually sold as steaks (cut crosswise). They are flaky and tender, with a mild, sweet taste.

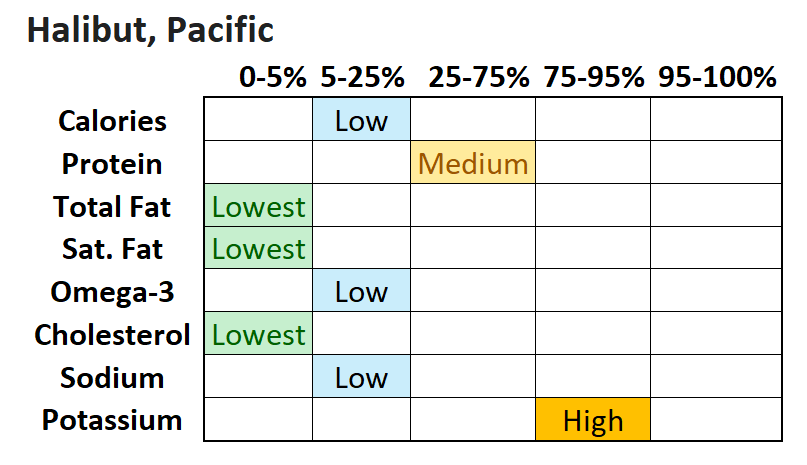

Health: Halibut is low in calories, mid-range in protein content, and very low in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol.

Stevens Palatability Index: Halibut is one of my favorite fish (SPI rating of 4.5). Whenever I visit Alaska, one of the first meals I look for is a fried halibut sandwich.

Atlantic Halibut H. hippoglossus supports a much smaller fishery in the United States, with landings of only 60,000 lbs, worth about US$400,000. Seafood Watch suggests to Avoid Atlantic Halibut from New England, due to overfishing.

Rights-Based Management

Pacific Halibut are managed using Individual Transferable Quotas, or ITQs (though fishers just call them Qs). Prior to 1995, halibut and many other fisheries were managed using a single overall fishery quota. This type of “Olympic” fishery was a zero-sum game. Access was unlimited, any boat could catch fish, and 3350 boats participated in the fishery. When opening day came, everyone went fishing, regardless of the weather, and 25 million pounds of fish were caught in less than 24 hours. This was Derby fishing; you fish or you die. Or maybe both, because the weather in March in Alaska could be deadly, and many boats sank in bad storms. But you had to go fishing on opening day, or you wouldn’t get any fish. So many fish were landed in one day that boats raced back to the ports to unload, leaving a lot of untended gear on the grounds. Boats were lined up at the docks to unload for days, and fish sat on ice in the boats for up to a week before they could be unloaded. All that fish then came on the market suddenly, though some was frozen and sold later in the year. Nevertheless, it was a bad system for both the fishermen and the fish.

In 1995, the IPHC implemented one of the first ITQ systems in the United States. Fishers were allotted quota based on their previous three-year history of fishing. Some boats received large quota shares, and others very little, and no boat could receive more than 3% of the total quota. This was a highly controversial situation, and many fishers protested the system as privatization of a public resource. But the beauty of the system was that smaller boats, with less catch, and less efficient methods, could sell their quota to larger boats with more efficient fishing methods. Thus, by 2014, there were less than 1000 boats participating in the fishery, and the season lasted six months or more. Fishers could choose to go fishing on opening day, if the weather was good, as prices for fresh halibut would be high. Or they could wait for better weather, since they knew they would be able to catch their entire quota. Or they could wait until later in the season, when frozen stocks would have dwindled and the price for fresh fish would come back up. This system was also better for the consumer, because fresh halibut was available continuously for much of the year.

Individual quotas and “rights-based management”, which give fishers specific amounts of fish to catch, was a revolutionary system, but has now become the de-facto form of management in many fisheries. Quotas may be assigned to specific Captains, or to boats, or to “Sectors” (types of boats) or cooperatives (groups of boats). In Alaska, remote communities may receive Community Shares, which allow them to catch fish in their area that otherwise would have been caught by vessels from Seattle or Kodiak. They can lease the shares to other boats or require that the fish be brought to shore for local processing. This has been a major source of income for many remote communities such as St. Paul, in the Pribilof Islands.

Just for the Halibut

Some people don’t like flounder because of its mild (e.g. lack of) flavor, or its abundance of small bones. But flounder is one of the best fish you can eat, and one of the most sustainable fisheries as well. Whenever I can get locally caught flounder that is fresh and hasn’t been frozen, I know it will be one of the best meals I could choose. Even better if topped with a pile of blue crab meat.

NOTE: Paid subscribers will receive a separate post with a savory seafood recipe for Halibut.

Writing about nature is not easy. It requires preparation, hard work, and sometimes sweat to observe nature, and time, thought, and effort to describe it. Not to mention eating all those seafood dinners. Although this post is free, becoming a paid subscriber will help me continue to share my thoughts, and encourage future postings.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.