#24-1. Sex and the Single Snail

In which the E@L explains his fascination with sex, snails, and spirals

Dear Reader: To my great surprise, the Ecologist at Large was selected for inclusion in this week’s “Substack Reads”. This is quite an honor for me, and it must be due to recommendations from you, my readers. So, I want to thank you for reading and sharing my posts.

This being the first post of the New Year, you might expect me to share some annular epiphany with you. Sorry to say, I do not have such a message. For one thing, my life tends to follow the rhythms of the tides and lunar cycles more than those of the sun and earth. When I began writing this column, I was focused primarily on sharing my scientific knowledge and experience. But my reader statistics indicate that the greatest response has been to posts that are more reflective and share my internal responses to nature, rather than those that are more didactic and technological. This was a bit of a surprise to me, but I hope to put that information to use for future columns.

Speaking of the future (and 2024) the Ecologist at Large will be expanding. I have opened a pathway for readers to become paid subscribers to my work, as well as donate one-off contributions via Buy-me-a-Coffee. What will subscribers get?

I will be posting some longer-form articles for subscribers only, starting later this month.

A series of articles based on a class I am teaching, called Savory Seafood. Can you identify the fish on your plate? Do you know where it’s from? I’ll discuss different types of seafood, where it’s from, how it’s caught and processed, and whether it's sustainable and healthy.

In addition, there may be some videos and podcasts as well. Finally, I will schedule some live chats with subscribers at a later date (to be determined).

So, thank you again for your readership and following, and I hope I will honor you with even better writing. And now for the fun stuff….

Sex and the Single Snail

My life’s course was determined by a penis. Not mine! (or any of my predecessor’s) but rather the penis of a snail. At the age of 22, I had just started work towards my MS in Marine Biology at the College of Charleston (now University of Charleston), and was looking for a suitable thesis topic. I had intended to conduct research on oyster reproduction until I learned that it was impossible to distinguish their sexes by eye. So, I shifted my gaze towards another locally available organism whose gender was much easier to identify – conchs (actually whelks, a type of predatory snail). If (and that’s a big IF) you can pull the conch’s body out of the shell part way by grabbing the operculum (which, by the way, the snail really dislikes, and will resist you with all its strength), you will see that the males have a “penis” (actually an intromittent organ) on one side. In a large conch, it can be the size of a man’s finger. That made my job much easier and finalized my research topic.

But my fascination with whelks extends beyond their genitalia. The most fascinating thing about snails is their spiral shape.

The Sacred Spiral

What do snails have in common with galaxies, hurricanes, pinecones, sunflowers, and DNA? They all consist of spiral patterns. Of all the forms in nature, spirals are one of the most common. Their beauty lies not only in the graceful shape of the spiral, but in the mathematical precision with which it is formed. Because of the human fascination with natural forms, spirals are even deemed sacred in some religions, and spiral patterns can be found in sites of worship from Meso-America to the Vatican, to the great mosque of Samarra.

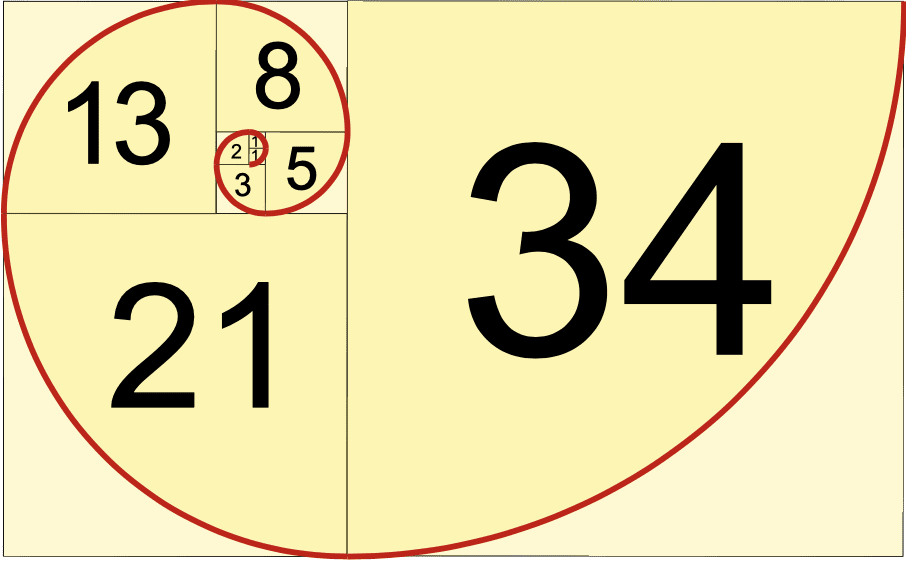

Simply put, a spiral is a curve that starts at a point and gets farther from the center as it revolves. What makes spirals unique among natural forms is that they are self-similar at all scales. In other words, every turn of the spiral has the same relationship to the one before it. Such spirals can be defined as logarithmic, and depend on the Fibonacci series or the Golden Ratio, called Phi, equivalent to 1.618 (more or less). A good explanation of spiral geometry can be found here, but allow me to paraphrase: The Fibonacci series is formed by adding each number to the one before it, e.g. 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, etc. The ratio of any number to the one before it is an approximation of Phi and gets more accurate as the numbers get larger.

You can create a Fibonacci-based spiral by drawing a series of squares, each with area equal to the squared numbers in the Fibonacci series (1x1, 2x2, 3x3, 5x5, etc), and place them sequentially next to each other, then draw a curve connecting each adjacent outside corner. Each time a square is added, it forms a rectangle for which the ratio of the length and width are equal to Phi. Not all spirals have the same rate of curvature however, but they can all be described by a logarithmic equation. A logarithmic spiral is equiangular, meaning that at any point on the curve, the angle between the radius and a tangent line is constant. There is a mathematical formula for this; I won’t bore you with at this point, but techno-geeks can check the appendix below.

Snailus sinistralus

While most higher organisms are symmetrical, snails demonstrate chirality, meaning that their shape cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, much like a pair of shoes. Most snails are dextral, or right-handed, because the whorl of the shell curves toward the right, in a clockwise manner, although a few species are sinistral, or left-handed. Many other biological structures exhibit chirality, such as amino acids; though most amino acids come in both right- and left-handed forms, only left handed, or L forms, are incorporated in living organisms.

The “handed-ness” of snails is inherited. Most species of snails are always righties or lefties, but some can be either/or. Chirality is determined during the very first cell division within the fertilized egg. In 2009, a pair of Japanese scientists were able to cause both left and right handed zygotes to reverse their chirality with almost 80% success. In 2019, using CRISPR, they determined that chirality in snails was determined by a single gene, called Lsdia 1, that is inherited from the their female parent (i.e, the “mother-snail”, though I’m not sure that term is appropriate in this context).

Jeremy’s Jeremiad

Unfortunately, the ability to change direction came too late for Jeremy, an English garden snail. Unlike their Japanese equivalents, English garden snails, Cornu aspersum, are always dextral. Except for Jeremy, who was by genetic accident born sinistral. Garden snails are hermaphroditic, producing both eggs and sperm, but rather than fertilizing themselves, they much prefer to mate with another snail (I mean, wouldn’t you?). They do so by snuggling (sliming?) up sideways to each other and injecting each other with darts containing chemicals that enhance their potential for fertilization. These aphrodisiac-bearing love darts affect the other snail both physiologically, by altering the contractions of the diverticulum, a tube through which sperm must travel, and behaviorally, by causing the partner to be less likely to remate with another snail. As a result, a darted snail is less likely to cuckold it’s darter.

In order to mate, however, garden snails must have their genitals on the same side. It’s impossible for a lefty to mate with a righty. Jeremy, being a lefty, was found by a scientist who sought mates for him from all over the country. Because they are so rare, only two other lefties were found, and both preferred to mate with each other rather than with Jeremy (Boo-hoo, I know). But one finally did, and, voila, all of his offspring were normal, right-handed snails, proving that Jeremy was really one of a kind.

My interest in snail sex led me to pursue a career in fisheries science, with a specialty in reproduction of marine invertebrates. After many years studying crabs, I eventually spiralled back to whelks. At the University of Maryland Eastern Shore I continued my research on conch reproduction with a specific set of questions: How fast do they grow, and can they change sex? Once again, a penis helped to answer that question.

To learn the rest of this story, and find out more about sex and the single snail, become a paid subscriber and read “All Conched Out” later this month.

This post is free for all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

Appendix

The equation for a logarithmic spiral, as described here, is r = aebθ, where r is the radius, θ is the angle from the origin (which can be >360 degrees), and a and b are constants. The constant b defines the rate at which the spiral expands, and it’s sign (+/-) defines the direction. You can go down many rabbit holes chasing the origin of this formula and solutions for a and b, but a good explanation is given by John D. Cook. I however, prefer to dwell on the shell.

Interesting.

I enjoy a piece I can learn from. Now I know more about snails than I ever did.

Congrats, Brad. I'm thrilled to see that you're getting traction on Substack (perhaps much stronger than a gastropod's adhesive locomotion)!