#25-16 The Incredible, Edible Oyster, Part 3: Aquaculture, Restoration, and Oyster Politics

In which the E@L explains triploidy, SOS (spat-on-shell), and how to shuck an oyster

“He was a very valiant man who first adventured on eating of oysters.” ― James VI

As we saw in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, oysters are a delicious and valuable food source that had been overexploited almost to the point of extinction during the 19th and early 20th century. Transplanted oysters from the Gulf of Mexico introduced several diseases to the Chesapeake Bay that further devastated native stocks. By the 1960’s, oysters in the United States had been seriously depleted.

1. Aquaculture to the Rescue

In the 1970s, scientists at the University of Washington and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science developed methods for artificial cultivation of oysters. Cultivated oysters could mature in 18-24 months, compared to 4-5 years for wild oysters. Growers in the Pacific Northwest tried cultivating the native Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida, but it was small and grew slowly. In Washington, Dr. Ken Chew introduced the Japanese oyster Crassostrea gigas for cultivation, but up to 70% of them succumbed to “Summer mortality", and their chalky, runny gonads made them inedible. To solve this, Dr. Standish Allen developed a method of producing triploid Oysters. Normal oysters (diploids) have two sets of chromosomes. Male oysters that were treated with chemicals or radiation developed four sets of chromosomes (tetraploid), and when mated with normal females, the offspring became triploid (three sets). Triploid oysters grew large and fat but did not reproduce, so all the energy went into growth. Triploid oysters are now used for almost all commercial cultivation because they do not spawn.

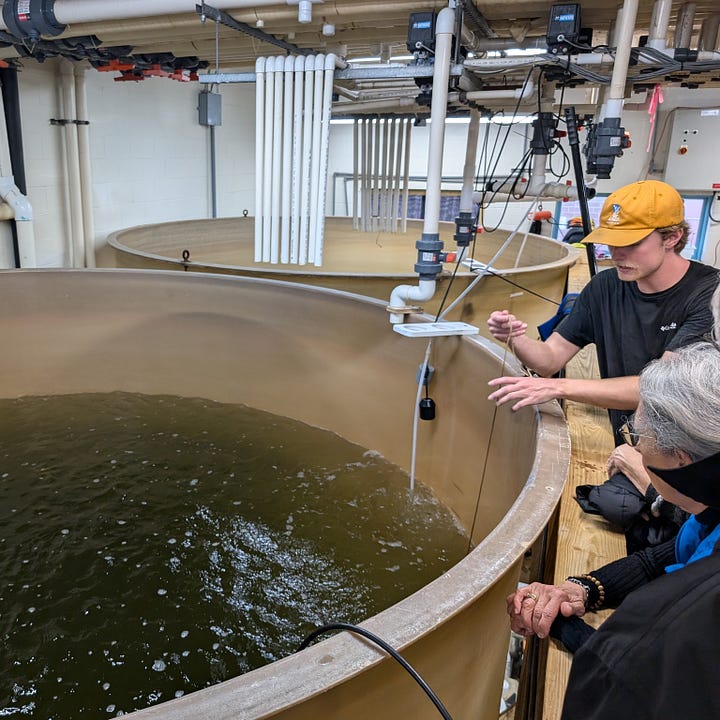

The University of Maryland Horn Point Laboratory (HPL) sits on a beautiful piece of property along the Choptank River. One of the largest buildings is dedicated almost exclusively to cultivation of oyster larvae. Starting in March, oyster broodstock are warmed up from their winter slumber and encouraged to spawn. Larvae are cultivated in large tanks and fed lab-raised phytoplankton. After a few weeks, the larvae are strained out and poured into large vats containing clean oyster shell on which they set and become spat-on-shell (yet another use for the acronym SoS).

In recent years, the HPL has produced over one billion spat. Commercial “farmers” buy small oysters from the lab and place them in trays (on bottom) or bags (floating) in shallow water. In the warm bay waters, they can grow to market size in 6 months (vs 2-3 years for wild). This is a completely sustainable type of seafood production. It has virtually no harmful impacts and helps improve water quality. About half of the oysters produced at the HPL are used to help recover and restore wild oyster populations.

Aquaculture is the future of oyster production around the world. Intense exploitation has driven most wild populations close to extinction, and few locations outside the US can support wild harvest. Few young people are entering the wild harvest fishery anymore, because it is hard work with a low profit margin. But many, including college graduates, are starting up aquaculture operations because it is seen as a successful and growing business opportunity. And oyster aquaculture is completely sustainable, unlike many other types of aquaculture. After spat production (from private or public hatcheries), the cost is primarily for equipment and harvesting. No artificial feeds are needed, and no chemicals are introduced into the food source. The only waste products are natural and are recycled by the surrounding ecosystem. And the oysters provide additional ecosystem services by removing excess nitrogen and creating habitat for other organisms. Oysters cultivated in cages are single, instead of being clustered together, providing a better product for oysters-on-the-half-shell. The primary obstacles for aquaculturists are obtaining leases, conflicts with waterway use, and occasional complaints from NIMBY neighbors who object to seeing floats or oyster trays in their viewshed, despite the beneficial effects for said water bodies (Yes, this was the reason a local landowner gave for objecting to his neighbor placing oyster cages in front of his own house).

2. Oyster Restoration and Anti-Restoration

Since colonial times, more shells were removed from Chesapeake Bay than were replaced, causing the Bay to become “shell-limited”. To rectify this, a major program of oyster restoration was begun in 2014. This work is organized by the Oyster Recovery Partnership (ORP) and conducted in partnership with the states of Maryland and Virginia, the Horn Point Lab, NOAA, the US Army Corps of Engineers, and commercial watermen. The goal is to set aside 20-30% of the known productive oyster habitat within designated oyster sanctuaries, including 50% of the 'best bars’, totalling almost 2000 acres. To this end, ten different sanctuary sites have been established in the Bay, five each in Maryland and Virginia. Each Sanctuary site received a base layer of clean shell, rock, or crushed concrete, after which SoS from the Horn Point Lab was placed on it. Restoration has cost about $110 Million to date, most of which are federal funds.

Oyster sanctuaries are off limits to commercial fishing. The major reason is to allow them to recover without disturbance, so that they will provide a source of oyster larvae and spat to other reefs and help improve water quality in the bay. Another reason is to conserve adult brood stock in sanctuaries. Federal agencies also wanted to assure that funds would support long term stability, and the reefs would not be fished out in a few years.

In other places, such as the Virginia barrier islands, oyster castles – stacking concrete blocks – are also used for restoration, with support from The Nature Conservancy. These are placed in long lines and depend on wild oysters to provide spat. Waterfront property owners can also help the Bay via Oyster Gardening, a kind of DIY Aquaculture. In the fall, each “gardener” receives 1000 to 2000 “seed” oysters, 1/4 to 1/2 inch in length, which are placed in mesh bags and held in floating rafts or suspended from docks. After a year, the oysters are used in repopulating natural reefs (sorry, you don’t get to keep them).

Restoration is not without controversy. Many watermen opposed creating or expanding the sanctuaries because they were off-limits to fishing. In 2025 they convinced two Maryland Republican legislators to propose legislation preventing the use of federal funds for restoration, hoping that would allow reversion to open access. But loss of federal funding would have shut down the Horn Point lab which produces about 50% of SoS used by the commercial aquaculture industry and currently can’t meet the demand for spat production. In fact, HPL provided more SoS for public fishing grounds than for the sanctuaries. Commercial oyster aquaculture is the fastest growing segment of Maryland seafood production and would be hamstrung without the hatchery. According to Ward Slacum, Director of the ORP, this legislation was short-sighted. The oyster industry, he said, was not just about the watermen; “it includes harvest, aquaculture, and restoration. There are jobs, income, and revenue on the line.”

Drs. Dave Nemazie and Mike Wilberg, both scientists at the University of Maryland, agreed with him. They were even more blunt, saying it was a terrible bill and an insult to all those who worked on restoration. The bill was anti-oyster, anti-restoration, and anti-Horn point. It would impede much of the work done by the hatchery and prevent the production of billions of spat per year. Many other projects at HPL would be defunded including research on oyster restoration success, ecosystem benefits, and nitrogen cycling in the Bay. Federal funding allowed restoration projects that were much bigger projects than either the States of Virginia or Maryland could support. In fact, the Chesapeake Bay oyster restoration project is the largest such project in the world, specifically designed to have the highest chance of success. To date, all measures of success (including survival of initial oysters and subsequent spat set) have been achieved. This was not believed possible prior to 2014. Placing limitations on how oyster restoration is accomplished would have crippled the program and prevented future options.

[Sidebar: After interviewing these professionals, in March 2025, your Ecologist @ Large was one of four people who testified against this legislation before both the Maryland House and Senate environmental committees, along with Dr. Nemazie and representatives of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Consequently, the bill never made it out of committee.]

In my home state of Maryland, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) manages oysters. Management goals include ending overfishing, increasing oyster abundance, increasing oyster habitat, improving water quality via filtration capacity, and ensuring sustainability. Maryland DNR surveys oyster spatfall every year by examining oyster shells around the bay and counting the number of spat found on all the shells in a bushel. In 2020 and 2023, they recorded the highest spatfall seen in almost 20 years, up to 87 spat/bushel. This was four times higher than the long-term mean. Spat were found in locations they had not been seen recently, including far up the Potomac River. DNR concluded that this was the result of an extremely dry year, with low rainfall leading to higher salinity in many parts of Chesapeake Bay. In 2024, the spatfall index was still above the 40-year median for the fifth consecutive year, and small oysters from the 2023 year-class were still abundant, having survived the high freshwater flows of winter. Oyster harvests in MD in 2023 were 723,000 bushels, of which 13% were provided by aquaculture.

3. Still Life with Oysters

As a neophyte graduate student, beginning work on my Master of Science in Marine Biology, I was interested in reproduction (of various sorts!) and how oysters used lipids (fats) during that process. But lipid physiology is related to sex, so I was stymied when I could not distinguish male oysters from female oysters. At which point I turned my attention to conchs, which have an obvious penis, making them easy to distinguish (The sordid details of which can be found in a previous post All Conched Out).

When I decided to pursue my PhD a few years later, I applied to the University of Washington, specifically to work with Dr. Ken Chew, the Guru of Pacific Oysters. The Olympia oyster Ostrea lurida, native to Washington, was small and not very productive. Dr. Chew had been instrumental in developing procedures for cultivating giant Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, from broodstock imported from Japan. These now form the basis of a multi-million-dollar industry on the Pacific Coast. Though interested in oysters, I eventually focused my dissertation research on Dungeness crabs (see A Crab for All Seasons). But I never lost interest in studying or eating oysters.

In 2015, The Nature Conservancy had offered me several hundred oyster castles to help enhance oyster populations within the Assateague National Seashore. After discussions with the National Park Service (NPS) and Maryland DNR, I was not convinced this would be successful due to lack of wild oysters, so I suggested we first conduct a survey of spat settlement. In 2018, the NPS provided me with a small amount of funds for research, so I recruited my last graduate student, Maddie Farmer, to undertake the project.

Maddie was one of the most industrious graduate students I ever met. She made hundreds of small square settlement plates out of PVC and ceramic tiles and placed them in the water from Delaware to Virginia (her skill with a band saw and drill press were amazing!). Over two years she diligently collected and replaced them every two weeks. Maddie had to overcome many obstacles during her work including COVID precautions that prevented her from sampling for six weeks, the destruction and removal of some of her equipment by vandals (even though it was labeled with county permits), and a hurricane that wiped out one sampling site completely. After recovering her plates, she counted all the oyster spat that had settled on them. She also counted everything else (barnacles, worms, hydroids, bryozoans, etc.) because we didn’t know if she would find any spat at all. But she did! Her results showed that spat settled mostly at the two inlets, Ocean City, and Chincoteague, but rarely anywhere else within the coastal bays. This suggested that the spat had originated from outside the system, most likely southern Virginia, and that enhancement within the bays was probably not feasible.

Assateague and Chincoteague Bays, however, do support a large oyster aquaculture industry, that cultivates oysters both on the bottom and in floating cages. Next time you order Chincoteague oysters, remember that they probably began life in the Horn Point Oyster Hatchery.

4. Oysters as Food

Looking at an oyster, it is easy to wonder: Who was the first person to ever eat an oyster? From the outside, they don’t appear to be something edible, and even once opened, they do not appeal to many people. But oyster afficionados know that oysters, whether raw, fried, or baked, are one of the most delicious seafoods available.

The shell itself seems impenetrable. It is indeed a fortress, evolved to protect the oyster from any number of outside attacks. It is also watertight, allowing the oyster to remain wet and cool even when exposed to air and weather during low tide. It consists mostly of calcium carbonate and some protein and is formed via a chemical reaction within the mantle, a tissue surrounding the oyster. It is no wonder that Rolex named their toughest waterproof watches “Oyster Perpetual”.

Inside the shell, what we mostly see are the gills, which filter the water for small particulates, mostly phytoplankton, that they can digest, though they also ingest bacteria and small microorganisms. Larger particles are encapsulated in mucous and rejected as “pseudofeces”. Surrounding the body is the mantle, that secretes the shell. Towards one end is the adductor muscle that pulls the shell together and holds it tight. On the other end is the gonad, that produces eggs or sperm, and stores much of the energy and fats that give the oyster its flavor. In between is the small digestive gland that may be green due to the phytoplankton contained within (don’t worry, it’s tots vegan).

Opening an oyster is no easy task. First, you must wear a tough glove (preferably leather) to protect your hands, both from the oyster and the knife. Hold the oyster with the flat side (the “top”) upward, then insert the oyster knife (a flat, rounded, dull blade) into the umbo, the area near the hinge at one end. If you can find a small niche, pry or twist it until the shell starts to separate. Then slide the knife towards the other end, keeping it up against the upper shell. This will cut the adductor muscle, allowing you to open the shell. Finally, slip the knife under the oyster and separate the muscle from the bottom shell, allowing it to slide out. If this is too much work, just put the oyster on a hot grill, or in the oven for a few minutes, until it starts to open (NOW you tell us?)

O Oysters,' said the Carpenter, You've had a pleasant run! Shall we be trotting home again?' But answer came there none — And this was scarcely odd, because they'd eaten every one." – Lewis Carrol

Oysters are extremely healthy food. They are low in calories, fat, sodium, and cholesterol. Oyster aquaculture is highly sustainable, though wild capture (dredging and tonging) is not. According to Seafood Watch, the Best Choice are cultivated oysters, or wild oysters from Delaware. Other sources of dredged oysters in the Atlantic region (MD, VA, NC, SC) are considered a Good Alternative. Most cultivated oysters are small, because they harvested at one year or less in order to be the right size for “cocktail” oysters served at buck-a-shuck bars, whereas wild oysters tend to be larger and older. I use those for baking.

And finally, the Stevens Palatability Index (SPI) is a resounding 5! I love raw oysters served on the half-shell with lemon or cocktail sauce. I also love oysters Rockefeller, baked with spinach and cheese. And I make a tasty oyster casserole, using a recipe handed down by my mentor, Dr. Ken Chew (Paid subscribers will get recipes in a separate email).

Bon Appetit! Oyster-dakimasu!

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.