A Crab for All Seasons (Sustainable Seafood #17)

Dungeness crab is the International Standard Ordinary Average Crab

Just Pinch Me

At the age of four, I was bitten with marine biology when a crab pinched my toe. Ever since, I have sought retribution by eating as many of them as I can. That’s actually a true story that I have often told to explain my lifelong scientific interest in crabs. But I learned only recently that it is also the origin story for the constellation Cancer.

Ghost Crabs in the Sky

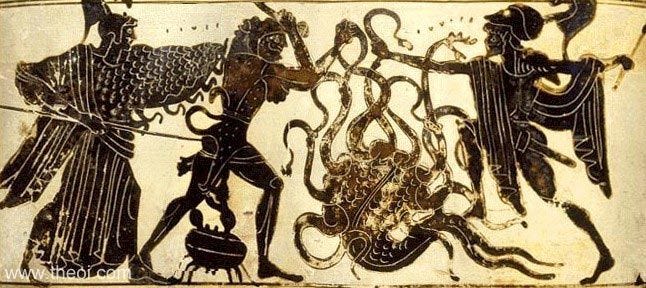

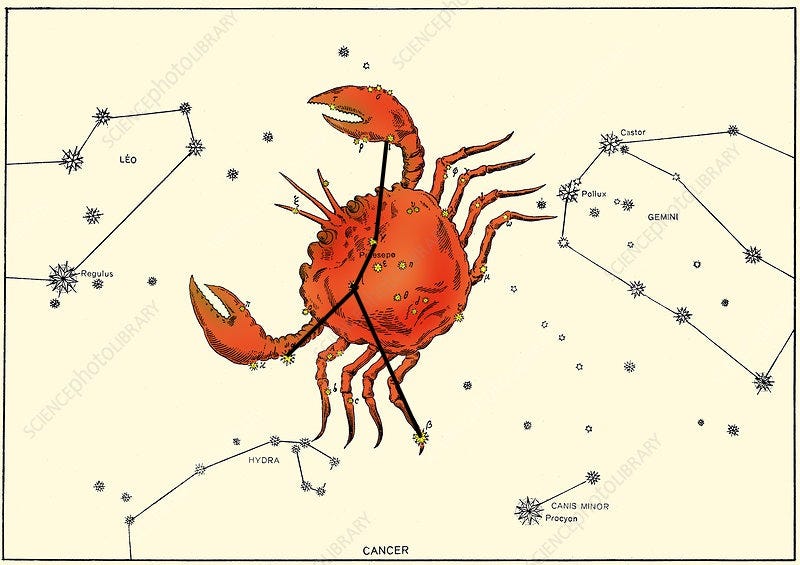

The story of Cancer originates in Greek mythology. According to Plato, who recorded the story in the fourth century BCE, or maybe just made it up entirely, the hero Hercules (aka Heracles) was given twelve tasks (or “labors”) to accomplish. After killing a great lion (which became the constellation Leo) as his first task, he was sent to kill the Hydra, a beast with nine heads (similar to the real Hydra, a marine organism with many polyps). He found her in the swamps of Lerna, but each time he lopped off one of Hydra’s heads, another would grow in its place.

“Dude,” Hercules said, “I should call this game Whack-a-Hydra”.

During the battle, the crab Karkinos (aka Carcinus or Cancer) pinched him in the foot, or the toe, or maybe somewhere else. Some pundits say Cancer was protecting his fellow swamp-dweller Hydra from a Herc-bashing, but others say he was bravely trying to warn Hercules about the futility of Hydra-decapitation. In the melee, Hercules somehow crushed cancer with either his foot or his club. Collateral damage, friendly fire, whatever. Either way, Cancer got a raw deal, so Hera, Zeus’s main squeeze and occasional antagonist, decided to elevate him, along with Hercules and Hydra, into the heavens as constellations. Why she gave equal treatment to the victor, the victim, and the vanquished is beyond us mere mortals to fathom. Such is our lot.

Nonetheless, that story accounts for four constellations, so it must have had some serious symbolism for the ancient Greeks. Or maybe they just thought it was a good story. Plato, so it goes, was also credited with looking at a dissected mass of diseased tissue and exclaiming “Yeesh, that looks like a bunch of crab legs. Let’s call it Cancer”. Then he downed an amphora of wine and congratulated himself on his smart-arsery. Thus, scientists who study crabs and other crustaceans, as well as those who study cancer the disease, are called carcinologists. And we also drink wine.

An International Standard

When the Swedish scientist Carolus Linnaeus (aka Charles Linne’ to his buds) got around to describing all of the worlds plants and animals (or so he thought) in 1758, one of the first animals he named was the common edible crab, Cancer pagurus. That was no real stretch because it is the most abundant and common crab around Northern Europe. Over 500 species of crustaceans were originally named Cancer something-or-other, but all but a dozen have since been reassigned to other genera. Still, because it is one of the most iconic and generic crabs, Cancer could be considered the International Standard Ordinary Average Crab. A crab for all seas and all seasons.

While Cancer pagurus is the European edible crab, North America has its own Cancrids. On the Atlantic coast, we have the rock crab Cancer irroratus and the Jonah crab Cancer borealis, though only the latter is eaten by humans. In the Pacific Ocean, the Dungeness crab Cancer magister is the target of a major fishery and the rest of this article; it was reassigned to the genus Metacarcinus in 2000, though this is still controversial. Other Pacific species include the red rock crab Cancer productus, the graceful Cancer crab Metacarcinus gracilis, and the Yellow rock crab Metacarcinus anthonyii.

Dungies or Dragons

Dungeness crabs, or Dungies, as they are known among fisher-people, range from Point Conception, California, to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, and have been found as far west as the Pribilof Islands. The name refers to Dungeness Spit, in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where the crabs are abundant. Dungeness crabs have ten legs (counting the claws, or chelipeds), as do most crustaceans in the order Decapoda (i.e. ten legs). Because all ten legs are visible, they are considered “true” crabs or Brachyurans, which means “short-tailed”, because the abdomen is straight and folded up beneath their shell. Hermit crabs and king crabs, on the other hand, have twisted, asymmetrical tails (abdomens), and only eight visible legs, so they are called Anomurans (“odd-tails”).

Adult Dungies migrate to ocean waters to breed in the fall. Their mating behavior is typical of brachyurans (another “standard”); males insert sperm packets into a pocket (the spermatheca) on the female’s sternum using an appendage (the gonopod) that operates like a syringe. They may also insert a plug to prevent the female from mating with other males. Later, females extrude a large clutch of up to 2 million eggs that become fertilized as they pass through the spermatheca, then attach to her abdomen. Females may bury in the sand until the eggs are ready to hatch in late winter.

After hatching, larvae drift offshore for several months while molting through four zoeal stages, then return to inshore waters as the last, or megalopa, stage. Juveniles tend to inhabit shallow inshore areas including bays and estuaries, eel grass beds, and oyster flats. Dungeness crabs molt multiple times per year until reaching maturity at about 3 years of age, after which they molt annually, if at all.

Like most crustaceans, Dungeness crabs can regenerate legs that are lost or damaged. A reflex reaction causes damaged legs to be autotomized, i.e. separated from the body. This happens at a specific location between two segments (the Basis and Ischium), where a membrane seals off the break to prevent blood loss or infection. In subsequent molts, the leg regrows with all remaining segments, but it may take three or more molts for it to regain normal size. This is not a problem for juvenile crabs, but adults may not live long enough to regrow lost limbs.

Dungeness crabs are omnivorous, eating a variety of foods including molluscs, worms, and shrimp, and can even catch small fish. They are also cannibalistic, eating smaller Dungeness crabs. Crabs are major predators of razor clams that may have ingested toxic algae that produce Domoic Acid, a neurotoxin. Although it is not toxic to the crabs, people who ingest it may develop a type of amnesia, thus it is termed “Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning”. For this reason, clam and crab fisheries may be closed when toxic algae are abundant causing millions of dollars in losses.

A Crab in Every Pot

Commercial fisheries for Dungeness crabs typically begin in late winter. Crabs can only be kept if larger than minimum size, which varies from 6 to 6.5 inches in different locations. Management uses the simple 3-S system, in which only males (Sex) above a minimum legal Size limit (MLS) may be caught during a specific Season (usually January-March in Washington). Some locations also control catch by limiting the number of traps that can be fished, and the number of crabs that can be caught per trip. In many locations, up to 90% of all recruits (crabs that reach the MLS) are caught in a season that may last only four to six weeks. In 2023, 46160 metric tons (102 million pounds) of Dungeness crabs were landed in US waters, worth over $272 Million.

Crabs are caught using cylindrical pots made of plastic-coated rebar covered with stainless steel wire. Pots are required to have escape rings for small crabs, and either a biodegradable (cotton mesh) panel, or section of twine that allows the lid to open. Nonetheless, derelict “ghost” traps that become lost can continue to fish for many years, trapping and killing hundreds of crabs.

Migrating gray or humpback whales often become entangled in crab trap lines; 34 humpbacks were reported entangled off California in 2024. Consequently, the Northern California Dungeness Crab season was delayed from its normal opening in December 2024 until January 15, 2025 due to the presence of whales migrating through the area. To help mitigate this problem, the State of California is proposing requirements for trap labeling and increased usage of pop-up (ropeless) traps (See The Trouble with Traps).

Dungeness crab landings tend to follow cycles of 8 to 12 years in Washington, Oregon, and California. This is probably due to variations in larval survival and return to estuaries, which may be associated with climate cycles in the ocean including the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and El Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). It may also be associated with changes in sea surface temperature, as higher temperatures cause reduced lipid quality in plankton that are consumed by crab larvae. Landings in Alaska are much smaller and tend to fluctuate inversely with those from the Pacific states, to fill demand. Crab populations are stable or increasing, as US landings have more than doubled since 1970. Seafood Watch considers Dungeness crab to be a “Good Alternative” because of the problems associated with ghost traps and whale entanglement.

Nutrition - Crabalicious

Dungeness crabs are usually sold as whole crabs, usually pre-cooked. Preparing them is just a matter of splitting them down the middle (creating a “section” of half a crab with legs), removing the inedible parts, and picking out the meat. An excellent visual guide to that process can be found here. If you are lucky enough to catch your own or buy them live, keep them refrigerated until cooking. You can cook them whole, but more will fit in a pot if you clean them first. Place the sections in a pot with a few inches of salted water, and maybe some Old Bay seasoning, and steam them for 15-20 minutes or until they turn bright red. Most people eat only the meat; some like to eat the yellow hepatopancreas or “crab butter”, but it can retain domoic acid or other pollutants, so I don’t advise it.

Dungeness Crabs are highly nutritious. Their meat is high in protein (for seafood), and low in calories, fat, cholesterol, and omega-3 fatty acids. They have moderate levels of sodium and potassium and are an excellent source of vitamin B12. The meat is chunky and firm with a slightly sweet flavor.

Stevens Palatability Index (SPI): 5. Speaking as a professional Carcinologist who has eaten many different types of crabs, IMHO the Dungeness crab is the best tasting crab in the world. It is simply Crabalicious.

Should you eat Dungeness crab? It’s a heart-healthy food choice, with few concerns about contaminants. Environmental concerns exist (ghost pots, whale entanglement), but are being addressed through increased regulation. And populations are increasing.

What do you think? I’d love to learn your opinion.

Writing about nature is not easy. It requires preparation, hard work, and sometimes sweat to observe nature, and time, thought, and effort to describe it. Not to mention all those crabs I ate. Although this post is free, becoming a paid subscriber will help me continue to share my thoughts, and encourage future postings.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.