A Deep Dive into Deep-Sea Mining, Part 1: A New Gold Rush?

In which the E@L delves into the history, politics, and exploitation of deep-sea minerals

Ecologist@Large Episode #25-25

A Nod(ule) to History

In 1875, the HMS Challenger, a three-masted sailing ship, ventured eastward across the Pacific Ocean conducting the first around-the-world scientific exploration of the ocean. Every so often it would stop, while scientists lowered a metallic dredge all the way to the bottom of the ocean over two miles below. They weren’t expecting to find much, as they didn’t believe any living organisms could survive the crushing depths, extreme cold, and lack of food at those depths.

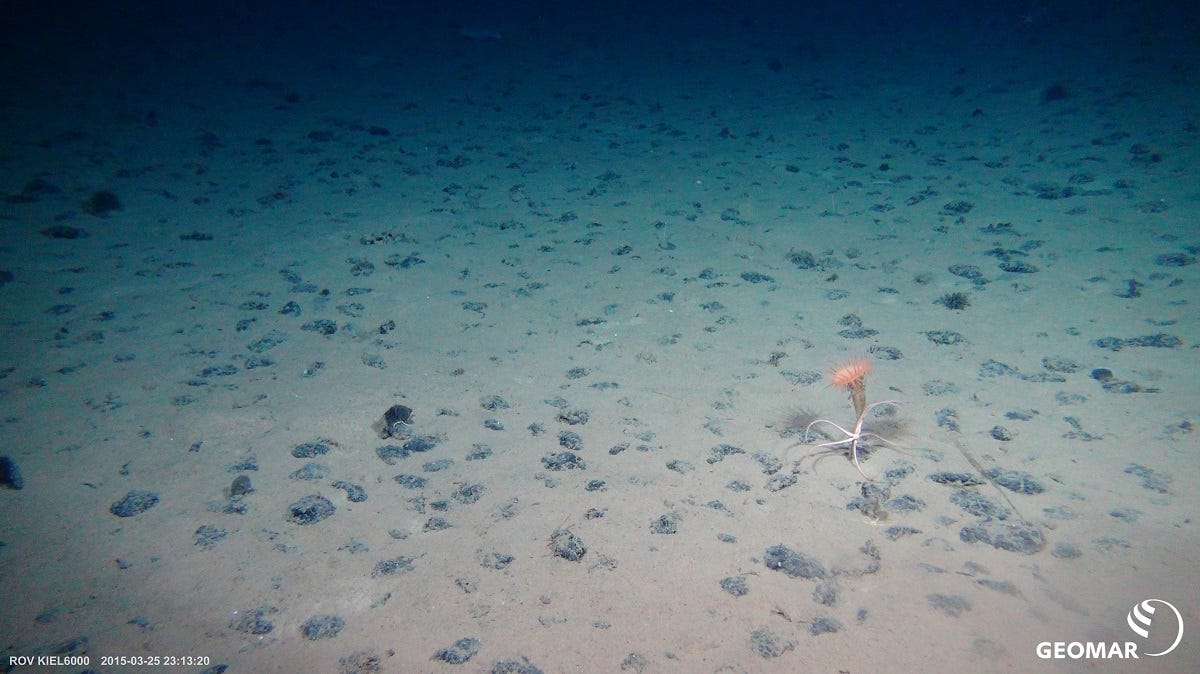

But when their dredge was retrieved, they were astonished to find not only living organisms, but also potato-sized metallic nodules, often with living organisms attached. As it later turned out, these polymetallic nodules consisted primarily of manganese (Mn), along with significant quantities of cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), and copper (Cu).

The practical uses of such nodules were unforeseen then but are now the basis of a major political and environmental controversy.

Because many countries and companies would like to mine them for their mineral content. The metals contained in the nodules are critical materials needed for building modern electronic components that will help us transition from an oil-based economy to one based on renewable energy. They are in high demand for use in everything from cell phones to car batteries to wind turbines. The total resource in the world ocean is estimated at 500 Billion tons. Let me repeat that: 500 BILLION tons. That’s more than twice the estimated amount of copper and manganese available from land-based resources.

China controls approximately 73% of the global cobalt resources. By 2030, China is projected to account for approximately 46% of the global cobalt supply. The ocean floor also contains a massive cobalt resource, over 7.3 billion tons, surpassing the world’s known land-based reserves by a factor of over 600. These are mostly found on seamount slopes, which also contain vital metals such as nickel and platinum.

But there are three major problems associated with harvesting polymetallic nodules from the deep sea. First, they have formed over millions of years and cannot easily be replaced; they are not a renewable resource. Second, they occur in some of the deepest parts of the ocean, among seafloor abyssal communities of living organisms about which we know virtually nothing. This has two sub-problems, being that a) the technology to retrieve the nodules is extremely expensive and still in development, and b) any effort to mine the nodules would probably have major impacts on those communities.

And thirdly, mining the seafloor requires agreements among nations about how to assign or claim specific regions and how to regulate the mining operations. None of which currently exists.

What’s Going on Down there? A Peek into the Abyss

Let’s take a descent into the abyssal ecosystem. The Abyssal zone of the ocean is defined as those parts of the seafloor from 3000 to 6000 meters depth (approximately 2 to 4 miles). The average depth of the ocean is 3682 m, and the Titanic lies at 3800 M. Most (90%) of ocean life and nutrients occur in the top 200 m of water, called the Photic Zone. Some nutrients sink below that in the form of waste products, but most are consumed by other organisms in mid-water. Few nutrients sink to the abyssal depths, where sediments accumulate at rates from 1 to 10 mm per year. As a result, the abundance and biomass of marine life is extremely low, although areas with metallic nodules have higher diversity than similar abyssal sites.

Organisms at abyssal depths are usually classified as Megafauna (organisms greater than 20 mm), including fish, sponges, anemones, urchins, clams, and sea cucumbers (holothurians), often called gummy squirrels or sea pigs. Macrofauna are smaller (from 3 to 20 mm), and include worms, amphipods, isopods, and snails. But we only know the identity of about 10% of abyssal fauna; 90% of them are undescribed. Of course there are also “charismatic megafauna” such as sharks, whales, and viper-toothed fish, but these are rare at such depths.

Abyssal communities are composed of many different species in varying numbers. The distribution of these communities is highly variable over both space and time. Unlike pelagic (sea surface) animals that spread larvae over hundreds of miles, recruitment of new organisms to abyssal populations occurs mainly via lateral migration of adults and juveniles. Thus, recovery of populations disturbed by mining to their “original state” could take decades or centuries.

A Political Hot (metal) Potato

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted in 1982 and many countries signed on in 1994. The United States, though, did not. We have our own rules but have usually followed their guidelines. As part of UNCLOS, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is supposed to develop the legal, financial and environmental framework for managing deep-sea mining (DSM) prior to any commercial exploitation. It was supposed to be completed by December 2025 but will likely be delayed.

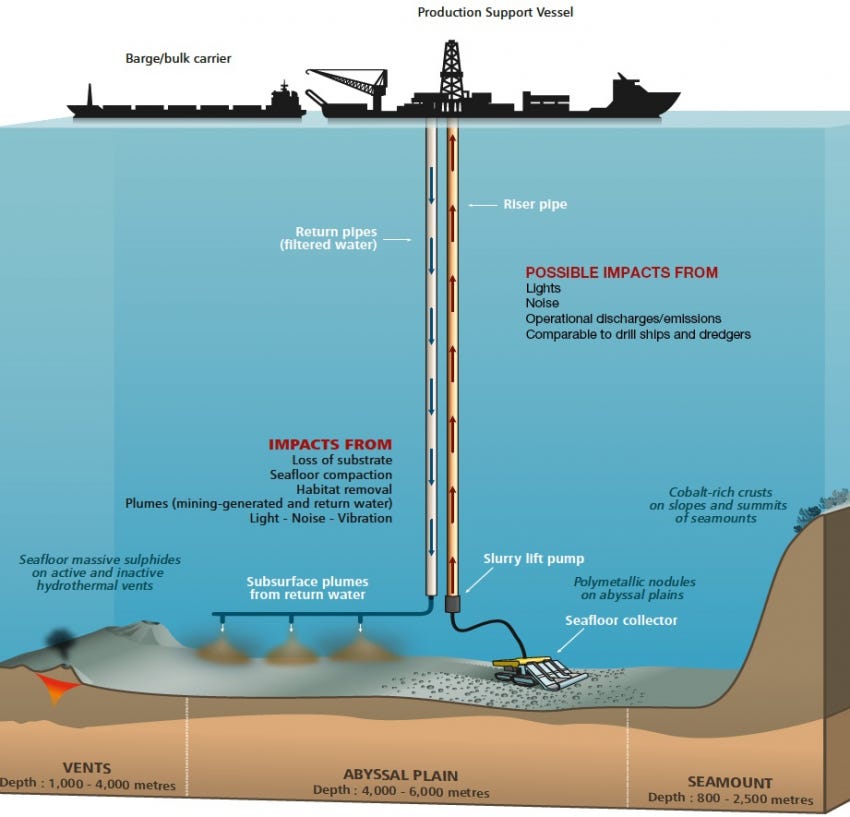

Some countries are asking for a moratorium on DSM to protect abyssal ecosystems. Independent scientists and Environmental groups such as Oceana, the Ocean Conservancy and GreenPeace support a moratorium on DSM because of its potential impacts on abyssal seafloor communities. These include removal of organisms and nodules on which they live, smothering by plumes, and concentration of heavy metals. Sediment plumes may contain toxic concentrations of heavy metals at their release point that could impact shallow water plankton or fish.

On April 24, 2025, President of the United States Donald Trump signed an executive order promoting deep-sea mining and ordering the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to fast-track permit applications. He sees this as a way for the U.S. to counter China’s dominance of global mineral supplies.

ISA Secretary-General Leticia Carvalho has criticized these actions by the US because they could destabilize national security and trigger diplomatic and maritime conflict. But the ISA has already issued at least 30 exploration licenses to companies in China, the UK, France, India, Germany, Russia, and Belgium that are interested in deep-sea mining, affecting 1.5 million square kilometers of seafloor. In 2013, the ISA granted China the right to explore a 3,000 square kilometer zone of cobalt-rich crusts in the western Pacific seamounts.

And the longer the ISA takes to create regulations, the higher the risk that nations will plunge into DSM on their own.

A Race to the Bottom

One area of particular interest is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), in the Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Mexico and Hawaii, which, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, may contain more nickel and cobalt than all known terrestrial reserves, possibly as much as 21 billion tons of nodules.

But the CCZ is an international zone, and many countries, including China, protested that mining there without authorization from the ISA would violate international law and set a precedent that any country (e.g. China) could do the same.

Japan, Norway, and other nations are also exploring the idea of deep-sea Mining. But after approving DSM in Norwegian waters in 2024, Norway’s Parliament changed track and placed a 4-year moratorium on DSM.

The U.S. is also considering allowing permits for DSM in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), a large area of ocean east of Guam and Saipan. But the CNMI would accrue no economic gain from DSM in federal waters, because profits from lease sales would go to the Federal Government, and there is no agreement for revenue sharing. The CNMI has asked the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) for an extension of the review period, but it has not yet been granted. Despite overwhelming opposition to DSM from residents of island territories, Congress can act without input from them and probably will.

In August 2025, the Cook Islands, a sovereign country, announced a partnership with the United States to advance research and development of seabed mineral resources. They estimate a resource of 12 Billion tons of nodules. Presumably any commercial profits would be shared with residents of the Cook Islands, unlike the situation in Guam.

Digging the Deep

The Metals Company (TMC) is one of many entities that would like to mine deep-sea nodules. They claim that the metals are critical for supporting the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Deep sea mining would also reduce the human suffering and ecological damage that accompanies the mining of cobalt and nickel on land.

TMC officially applied for approval from NOAA to begin commercial-scale mining in international (NOT U.S.) waters. Their permit request covers nearly 200,000 square kilometers of seafloor. TMC has promised to leave 15% of nodules on the seafloor for re-colonization of abyssal communities.

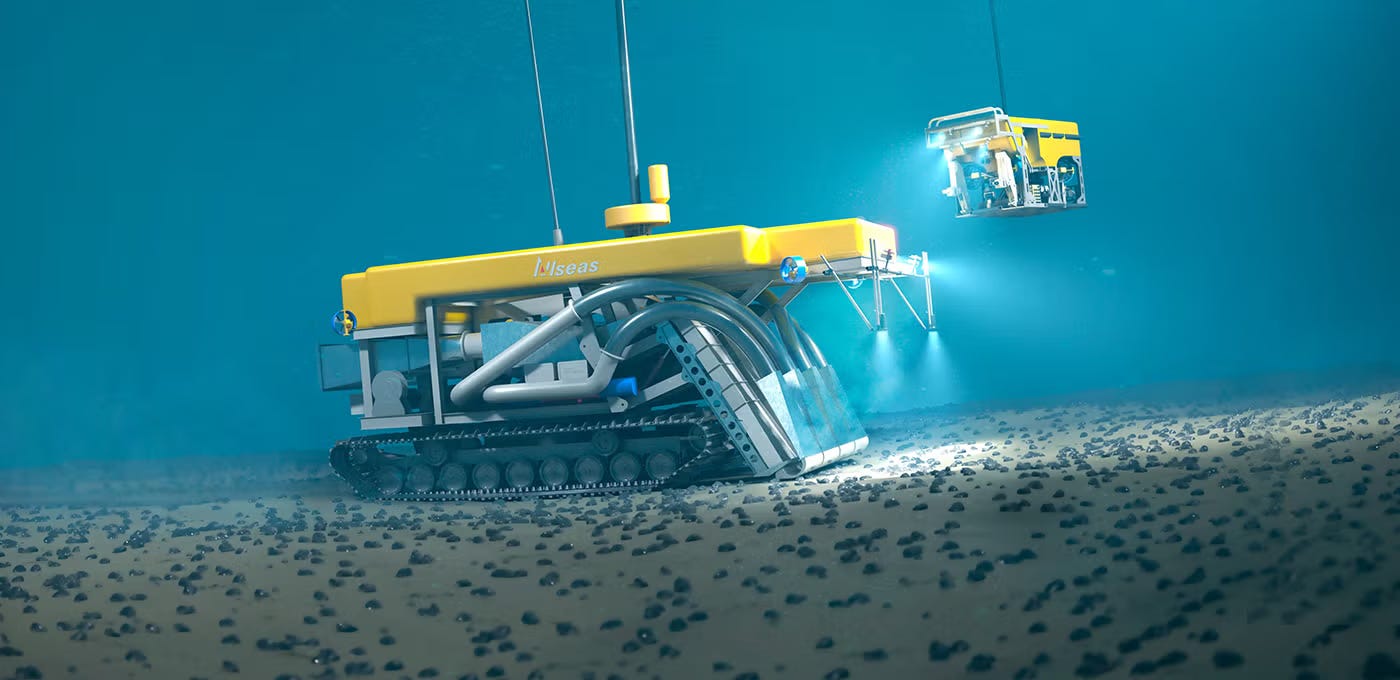

Collecting heavy metal potatoes from the seafloor requires a lot of technology and investment. The collecting device, or mining machine is a large device about the size of a Sherman Tank. It moves along the seafloor on tracks like a tank. A scooper digs into the seafloor and removes the top 2 inches of sediment (where most organisms are) along with the nodules.

Water and air pressure are used to push sediment and nodules up through a riser pipe in a slurry, at the rate of 200 tons per hour. After straining out the nodules, the water and sediment are discharged back to the ocean in a plume of sediment. The depth at which this is done is critical for determining seafloor impacts.

An individual mining site for deep-sea nodules could potentially cover an area of 400 km2 and be active for 20 yr. Impacts of mining could include mechanical disturbance, sediment compaction, removal of hard substratum and sediments that form habitats of deep-sea fauna, as well as killing or removing the fauna living there. Sediment plumes could extend the footprint for hundreds of meters beyond the immediate impact area.

The Pros and Cons

Proponents of deep-sea mining base their position on arguments like this:

DSM has a biomass imprint 300 times smaller than mining in rain forests

No child labor is used, as it is for mining cobalt in the Congo

DSM produces 90% lower atmospheric emissions than mining on land

No tailings or waste sludge are produced

No open pits are left behind

DSM is a source of new revenue and jobs

DSM will reduce dependence on foreign imports of critical minerals

The toxicity of discharge plumes would lessen as it disperses and dilutes.

In contrast, opponents of DSM make the following arguments:

Nodules are non-renewable (require millions of years to form)

DSM could release large quantities of stored CO2 from the seafloor

DSM could create long term, probably permanent impacts on fragile habitats

Sediment plumes will extend the impacts far beyond the DSM site

Disturbed areas may never fully recover, and some species may go extinct

We have little scientific knowledge of abyssal ecosystems

There is great potential for technical risks, accidents, and failures

Global regulations are weak or absent

Who benefits from DSM? Can profits be put into an International Seabed Sustainability Fund?

NI and Co are in over-supply; the industry is moving towards sodium-ion batteries that don’t use those metals.

Next Steps

All of these statements are true to some degree. But how can we determine the actual impacts of Deep-sea Mining on abyssal ecosystems? What are they? Are they negative, positive, or neutral? Can we mitigate them?

The scientists aboard the HMS Challenger who recovered a metal potato from the sea floor probably looked at it simply as a curiosity. They didn’t imagine the potential uses of such a thing, the controversies that it would stimulate, nor the problems that might accrue from a mad rush to find more of them.

Assessing the ecological impacts of deep-sea mining will be the subject of the next post from your Ecologist@Large in Part 2 of this series.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

For a good look at the mechanics and controversy over deep sea mining, take a look at this 21-minute video on YouTube. It is admittedly a bit pro-industry, but still quite informative.

Thanks for your comments. Jason Anthony published an earlier article on this subject in which he looked more closely at the potential demand and economics. https://jasonanthony.substack.com/p/still-digging-9d7

My next article on this subject will focus primarily on detection and magnitude of ecological impacts.

Solid overview of the tradeoffs, but the temporal asymmetry really stands out: nodules take milions of years to form, yet we're debating 20-year mining leases. The argument that leaving 15% behind enables recolonization misses the point that recovery timescales at abyssal depths are measured in centuries, if at all. And the bit about sodium-ion batteries potentially displacing nickel and cobalt demand feels kinda understated, could undermine the whole urgency framing if those alternatives scale up faster than ISA regs get finalized.