#6. Horseshoe Crabs, Part 2: What’s a crab worth?

What is the best use of this natural resource: bait, pharmaceuticals, or ecotourism?

In Part 1 of this series we discussed the biology of horseshoe crabs, their ecological value as a food source for migrating shorebirds, and the fisheries that harvest them for bait or as a source of Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate, a valuable pharmaceutical product. In Part 2, we investigate the mortality of horseshoe crabs, their economic value, and alternative options for sustainable management.

Horseshoe crabs on a beach in Maryland (B. Stevens).

How many horseshoe crabs are we killing?

The mortality of horseshoe crabs from bleeding operations has been estimated to range from 4% to 30%, mostly due to differences in industry methods, with an average of 15%. A large portion of this mortality, however, may be due to the stress caused by handling, transport, and temperature exposure, and not to the bleeding process. These numbers do not account, however, for changes in behavior that may occur after release of the crabs, such as disorientation, or the disruption caused to spawning activity.

A longer-term analysis of recaptured tagged horseshoe crabs came to the somewhat surprising conclusion that bled crabs had higher survival (68%) than unbled crabs (51%). Although this seems counterintuitive, it might simply be due to the fact that crabs selected for bleeding tend to be the youngest and healthiest crabs. The same study found that bled crabs returned to beaches at lower rates than unbled crabs, however, indicating that they may be less active in mating.

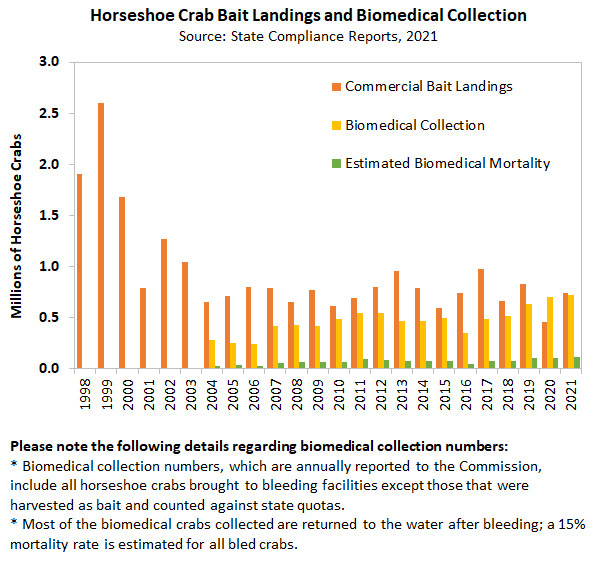

In 2019, over 1 million horseshoe crabs were harvested for bait coastwide, including 250,000 male and 10,000 female crabs from the Delaware Bay population alone. In addition, bleeding operations killed an estimated 118,000 more. The number of crabs harvested for LAL production rose significantly in 2020, and for the first time almost matched the number of those harvested for bait. Together, these numbers only comprise about 1.5% of the Delaware Bay population, however, so it is unlikely that fishing at current levels has a major impact on horseshoe crab populations.

Numbers of horseshoe crabs harvested for bait and pharmaceutical production (Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission)

Managing Horseshoe Crab Harvests

In the United States, horseshoe crabs are managed by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) using an Adaptive Resource Management (ARM) Framework developed in 2009, which is updated annually with new population estimates for both horseshoe crabs and red knots in the Delaware Bay region.

The original ARM Framework was based on outdated biological information and did not include mortality due to bleeding or discards from other fisheries. Furthermore, the ARM was designed to optimize the harvest of all horseshoe crabs regardless of sex or the status of red knot populations. Due to these limitations, an updated ARM was developed in December 2021 using a new population model that incorporated updated, locally relevant biological information as well as these additional mortality sources.

The revised ARM, known as Addendum VIII, was designed to optimize the harvest of male and female horseshoe crabs independently, as well as the abundance of red knots. The long-term goals of management are to increase the number of female horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay population to a minimum threshold of 11.2 million, and red knot passage numbers to a threshold of 81,900 birds. As of 2019, there were an estimated 21.9 million male and 9.4 million female horseshoe crabs, and 45,000 red knots passed through the Bay. So both female horseshoe crabs and red knots are currently below the minimum levels required to allow harvest of female horseshoe crabs.

In the previous ARM Framework, harvest of female horseshoe crabs was prohibited until minimum population levels were attained, after which maximum harvests of 210,000 females and 500,000 male crabs could have occurred. Such a “knife-edge” all-or-nothing control rule did not provide room for discretion in the number of females to harvest. The revised ARM allows female crab harvest to vary along a sliding scale, thus providing much more versatility in management decisions. Nonetheless, the updated analysis suggested up to 140,000 female horseshoe crabs could be harvested sustainably from the Delaware Bay population. If implemented, this would be a radical departure from the previous practice of not harvesting female horseshoe crabs.

Horseshoe crabs are commonly caught as bycatch when dredging for knobbed whelks (B. Stevens)

Should we be harvesting female horseshoe crabs?

While this outcome might be applauded by the conch fishing industry, it has bird lovers up in arms (wings?). According to minority opinions written by Dr. Larry Niles and Wendy Walsh, the proposed harvest of female horseshoe crabs does not provide adequate protection for shorebirds or inclusion of climate change impacts, especially the effects of altered wind, wave, and temperature conditions on egg deposits. Conservation of red knots requires a “superabundance” of surface-available horseshoe crab eggs, yet after 20 years of restricted crab harvest, the abundance of surface eggs is currently one-fifth of historic highs. Although the number of birds passing through Delaware’s beaches is stable, the peak number (7000) observed on a single day in 2020 was the lowest in twenty years. Niles and Walsh recommended that females should not be harvested until a public review process was held, and the revised ARM had been tested over several years.

From the perspective of bird advocates, every horseshoe crab egg is critical. Dr. David Curson, Director of Bird Conservation in Maryland for the Mid-Atlantic Division of the National Audobon Society, suggested that Audobon would like to see a complete moratorium on horseshoe crab harvesting in Delaware. Although any State can choose not to harvest female crabs, Audobon would like to see more than just an ad-hoc halt to harvesting.

“Fishermen will tell you it’s about their jobs”, Dr. Curson said. “But the ecotourism industry employs more people than the conch fishery and is probably more valuable. Fishermen may complain about losing money but think about all the hotels and restaurants that are used by tourists, and all the people they employ. It makes no sense to use such a valuable natural resource for bait, to catch conch that are shipped halfway around the world”.

In November 2022, after public review of the proposed Addendum VIII, the Horseshoe Crab Management board decided not to allow harvest of female horseshoe crabs, and set 2023 harvest limits for horseshoe crabs of Delaware Bay origin at 475,000 male crabs and zero females. However, not all horseshoe crabs originate from Delaware Bay, so additional harvests of 85,327 male HSC were allowed in Maryland and 20,333 male HSC in Virginia. But for now, female harvest is off the table.

Fisherman catching channeled whelks in traps (B. Stevens)

What is a horseshoe crab worth, anyway?

The value of horseshoe crabs and red knots to the ecotourism industry is virtually impossible to estimate. Conch landings, though, can be estimated from NOAA fisheries data. Several species of conchs are landed in the Northeastern United States (Maryland through Massachusetts) but only channeled whelks (Busycoytypus canaliculatus) are trapped using bait. From 2011 to 2020, an average of 945,000 lbs of channeled whelks were landed annually in the Northeast US, with a value of $7.1 million, while an average of 437,440 Delaware Bay horseshoe crabs were harvested for bait. If we assume that all of the horseshoe crabs used for bait came from this population, and all the bait was used to catch conch, then each crab brought in 2.16 lbs of conch, worth $16.24. These assumptions may not be completely accurate, but they get us in the ballpark. During that same period, the US LAL industry harvested about 500,000 crabs annually and killed an average of 80,000, but the number of Tachypleus crabs bled and killed is unknown. If the US industry was worth even half of the total $200 million, each horseshoe crab bled in the US would be worth about $200, and each dead one about $1250. Clearly, horseshoe crabs are worth a lot more to the pharmaceutical industry than to the fishing industry.

But what if we were to stop seeing horseshoe crabs as a commodity for exploitation and start seeing them as critical components of the ecosystem? Shouldn’t it be enough to appreciate them simply for that? This is an animal that has existed essentially unchanged for over 200 million years, requires nine to ten years to reach adulthood, has extremely high mortality from egg to adult stages, and easily qualifies as “charismatic megafauna”.

The relationship between horseshoe crabs and shorebirds has evolved over eons. In contrast, their relationship with humans has been relatively brief, but our impact has been substantial. We are now faced with difficult questions regarding the future of horseshoe crab and red knot populations. Should we harvest female horseshoe crabs for bait or LAL production? Should we ramp up research into alternative sources of bait and LAL? Should we enact regulation to enforce improved crab handling and LAL production? Should egg production for bird food be prioritized? Should we be harvesting any horseshoe crabs at all? What is the best use of this resource? Will the horseshoe crab fishery eventually go the way of the whaling fleets, as we transition to alternative resources?

Answering these questions will require engaging a broad spectrum of stakeholders and interested parties, evaluating conflicting goals, and making difficult choices. Even though alternatives to LAL are being developed, the best course of action for the time being is probably to increase and improve handling and conservation methods for horseshoe crabs.

Where can we see horseshoe crabs and red knots?

As we delve into the minutiae of this decision-making process, we should not let it overwhelm our reverence for this natural phenomenon. Residents of the mid-Atlantic are in a unique position to observe the annual rite of horseshoe crab spawning and feeding on their eggs by thousands of migrating shorebirds. It behooves all of us to take the opportunity to appreciate this wonderful ecological interaction at work.

In the Mid-Atlantic region, one of the best places to see spawning Horseshoe Crabs and Red Knots is the DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor, DE. For a closer look at them, try Slaughter Beach or Bowers Beach. Another hotspot further south is the beach at James Farm Ecological Preserve near Bethany Beach (but few red knots feed there). The best time to observe both red knots and horseshoe crab will be during the late evening high tides under new and full moons from May through early July. Scientists and volunteers will be out surveying them to estimate population abundance, and you may even see them doing this.

Crab watchers look for mating horseshoe crabs at Slaughter Beach, DE (B. Stevens)

As you wander the beaches looking for horseshoe crabs, watch out for stranded crabs. Stranding is one of the major causes of mortality to adult horseshoe crabs, and it is common to see crabs lying upside down, where they quickly become attacked by seagulls. If you do see a stranded crab that is alive, don’t pick it up by the tail, as this could harm the crab. Instead, turn it over gently and try to place it back in the water. This simple act of compassion can save countless crabs.

On one such night last May, a group of a dozen or so eager crab-watchers accompanied me to Slaughter Beach, DE. We arrived a bit before high tide as the crabs were just coming in, so they weren’t yet quite carpeting the beach. Every few yards we found coupled crabs in amplexus, with an amorous male clinging to the tail of his intended mate. While we marveled at this ancient mating ritual, another similar ritual played out before us. A teenage girl and boy frolicked in the waves not too far away, clinging to each other in a different kind of amplexus, following the urge of their hormones, ignoring the world around them. How their amorous engagement might be rudely interrupted, I thought, if they accidentally stepped on the sharp-spined tail of a horseshoe crab. But as far as I could tell, they were oblivious of both the crabs and the people watching them. As ever it should be.