Snapper and Rockfish (Sustainable Seafood #16)

When is a red snapper not a “Red Snapper”?

If it looks like a snapper, and it’s red, it’s a red snapper, right? No, probably not. A 2013 study by OCEANA found that 89% of fish labeled “red snapper” were not that species; 20% were another type of snapper, and the rest were not even in the snapper family. Most of the mislabeled fish were either Pacific rockfish (Sebastes spp), or Tilapia, which accounted for over half the “snapper” sold in sushi restaurants. All “snapper” samples from Washington, DC, were mislabeled. This fishy injustice lies somewhere on the spectrum from outright fraud, through willful ignorance, to benign negligence (See Sustainable Seafood 4).

To Snap or Not to Snap

Snappers belong to the Family Lutjanidae. They have a sloping head, a small mouth, and a lunate tail, shaped like a crescent moon. Snappers are highly valued sportfish, and management is highly contentious. The snapper family includes many species; up to nineteen are identified in US catch data, but the Food and Drug Administration allows 47 different species to be sold as “snapper”. Red snapper is the most common species, comprising 65% of the catch of real snappers, followed by Yellowtail Snapper (15%), Vermilion Snapper (13%), Gray Snapper (2%) and Mutton Snapper (1%).

Red snapper comprises only a single species, Lutjanus campechanus. It is one of the most sought-after gamefish in the Gulf of Mexico. They are heavily regulated in the US, and decisions affecting allocation of the catch between recreational and commercial fishers become highly controversial. In US waters, red snapper are managed as two distinct stocks, one being in the Gulf of Mexico, and the other in the South Atlantic region of the US (Florida to North Carolina). However, other species that are sold as “red snapper” include Bocaciao (a type of west coast rockfish, see below), and Enaga (Etelis coruscans), a fish from the southwest Pacific Ocean otherwise known as Flame Snapper or Longtail Snapper. Neither of these is a true snapper.

Where: Red Snapper are abundant throughout the Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic region of the US. They live around reefs and wrecks to 600 feet depth.

FAQs: Red Snapper can reach 40 inches in length, 50 lbs in weight, and live up to 50 years. They eat fish, shrimp, crab, and squid, and are prey of jacks, grouper, and sharks. Those living in deeper water tend to be darker red. Many have canine teeth, from which they get the name “snapper”.

Status: Populations of Red Snapper in the Gulf of Mexico are healthy, but those in the South Atlantic region are overfished, and were closed to harvest for several years prior to 2016.

Fishery: Fishers use mostly vertical hook and line gear; commercial fishers use powered reels to bring fish up from deep water. The fishery in the Gulf is managed using Individual Fishing Quotas. In 2022, commercial landings were 7.5 million lbs, worth $35 million, while recreational landings were about 15 million lbs. Red snapper brought up from deep water often suffer from barotrauma which causes the stomach to evert and the eyes to bulge out, and may cause high mortality in sublegal fish that are discarded. Mortality can be reduced by venting the gas bladder or using a descender which takes the fish to the bottom rapidly and releases it. Fishers are required to use circle hooks in some areas to prevent discard mortality.

Nutrition: Snapper have medium to high protein levels and very low fat. They are high in minerals like potassium.

Pacific Rockfish - The Non-Snapper

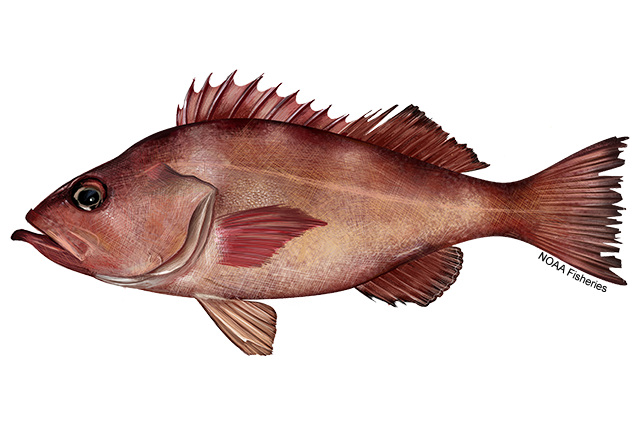

On the US Pacific Coast, one of the most common types of fish are Pacific Rockfish. Rockfish are not related to Striped Bass which are called rockfish in Chesapeake Bay. They are actually members of the superfamily Scorpaenoidei, which includes the scorpion fish and bullheads. Most Rockfish are members of the family Sebastidae and genus Sebastes. A similar fish in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean is called redfish Sebastes fasciatus.

Where: Over 50 species of Sebastes are landed, from California to Alaska. Rockfish live in deep water along the continental slope and shelf break. They are usually found along rocky bottoms and ledges.

FAQs: All Rockfish are extremely spiny. They have a protruding lower jaw. Many reach 20 inches or more, and 4 to 20 pounds, though some can exceed 30 lbs. Some Rockfish can live to 100 years of age. Rockfish are viviparous, meaning that they give live birth. After fertilization, the eggs hatch inside the mature female, and the larvae wriggle out of her and begin swimming. Rockfish eat krill (Euphausids), and small fish including other Rockfish. They are prey of rockfish, lingcod, halibut, and sperm whales. Rockfish come in many colors, some of which are red. These may be mislabeled and sold as Red Snapper, even though they are not closely related. If you are dining on the West Coast and see Red Snapper on the menu, it is most likely a Pacific Rockfish.

Fishery: The majority of Rockfish landings (77%) are Pacific Ocean Perch Sebastes alutus; Widow Rockfish make up 13%, Yellowtail 6%. Others include Black Rockfish, Chilipepper Rockfish, Canary Rockfish, and Bocaccio. Many are caught by trawls, in which multiple species are mixed together. These may be filleted at sea, so by the time they return to shoreside processors, they cannot be identified to species. Rockfish are popular recreational fish, where they live close to the shore (especially in Alaska). A typical rockfish can produce anywhere from 2 to 10 lbs of filets.

Status: Rockfish populations on the US West Coast are not overfished.

Health: Rockfish have firm, meaty, white flesh. They are excellent baked or grilled, or cooked en papillote (wrapped in foil). (NOTE: Paid subscribers will receive a separate email with a recipe for Pacific Rockfish).

SPI: 4.0 Rockfish are one of my favorite Alaskan fish, both to catch (on rod and reel) and to eat.

Whether you eat real Red Snapper, or Pacific Rockfish, you are in for a healthy and delicious meal that will have you coming back for more.

Writing about nature is not easy. It requires preparation, hard work, and sometimes sweat to observe nature, and time, thought, and effort to describe it. Not to mention all the time spent testing seafood recipes! Although this post is free, becoming a paid subscriber will help me continue to share my thoughts, and encourage future postings.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.