Sustainable Seafood 4. What's that Fish? Fish Fraud or Seafood Mislabeling?

In which the E@L finds fault with fishy seafood names

As I parked in front of the restaurant, I noticed the signboard with the day’s special: “Scallop Linguini”. “That’s for me”, I told my wife. But when it came to the table, I knew something was fishy. “These don’t look like scallops”, I said. Slicing into one with a knife showed that the muscle fibers ran horizontally instead of vertically. “They’re skate wings”, I said. I don’t dislike skate wings; I’ve ordered them before and they were fine. But to be served skate wings disguised as scallops is simply fraudulent.

I called our server over and told her I didn’t think my “scallops” were real. “Oh, they’re the same scallops we always buy”, she told me, so I asked her to send over the manager. “I’m a professional fishery scientist”, I said, “and these are obviously skate wings. Selling them as scallops is illegal.” He shrugged and admitted it but said he didn’t think anybody would notice the difference. After finishing our meal and going home, I wrote a scathing review on Yelp, to which he replied with an offer of a free meal. Too little, too late. I would never eat there again.

Seafood Roulette

Seafood processing has many different stages, during which it can change form from raw and whole to filets, chowder, cooked, canned, cakes, or cocktails. Supply chains are extremely complex and opaque, making it difficult to trace the origins of wild seafood because of the mixture of species, locations, and sources from whence it comes. This often leads to confusion about its identity.

Many types of seafood are known by ambiguous generic names such as cod, snapper, or grouper, which could be any one of 50-200 different species, some of which may be endangered or non-sustainable. Fishers, processors, distributors, and retailers may all have a different name for the same fish. Although most seafoods have names that are accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the names under which they are sold or marketed are often incorrect or misleading. Thus, it is often difficult or impossible to determine what species is being sold, or where it is from. Consequently, choosing seafood is often a gamble with unpredictable outcomes.

This lack of consistency produces a continuum of misinformation and confusion. At one end of the spectrum is the specific scientific or Latin species name, usually assigned by scientists, and published in a scientific journal. These are always written in italic, with only the genus capitalized, as in Genus species. Many of these are published by the American Fisheries Society (AFS) in thick books; there is one book for fish, one for crustaceans, one for molluscs, etc [1] . Next is the common name, which may also be approved by the AFS. Then there are local names that may vary with type or size of fish, such as bunker, scrod, or fluke. Then there are trade names that are often made up, such as monkfish or butterfish. In some cases, the retailer or distributor may not really know what they are selling due to a lack of information and may mislabel it unintentionally. But many fish are intentionally misidentified and sold under incorrect names, such as red snapper. This can be considered outright fraud. It is usually the case that a less popular, or less expensive fish, or non-sustainable fish is sold as a more popular, more expensive fish. Thus, skate wings for scallops.

When is a snapper not a snapper?

The conservation group OCEANA conducted a study of seafood mislabeling in 2013. They collected 1,200 samples of seafood from 674 retail outlets in 21 states, then applied DNA testing using PCA technology that was available in 2010. This was not a true scientific study, though, and there are many caveats. Only fish were sampled (no shellfish). The samples chosen were not selected using random or representative sampling (e.g. in proportion to quantity sold). Instead, the investigators focused on species that were known to be commonly mislabeled. They found that 33% of their samples were mis-labeled. This is almost certainly overestimated, and not representative of all fish available, because of their focus on selected species. A similar study conducted by the FDA, using random sampling methods, found only 15% of samples mislabeled, almost all of which were snapper or grouper.

Nonetheless, OCEANA’s investigators concluded that 74% of the mislabeled products were actually a less valuable species. The most commonly mislabeled products were snapper (89% mislabeled) and Tuna (59%). Even though FDA regulations allow 47 different species to be sold as “snapper”, almost 90% of fish labeled “snapper” in restaurants or grocery stores were mislabeled; about 20% of this was another type of snapper, but the rest were not even in the snapper family (Lutjanidae). Most of the mislabeled fish were either Pacific rockfish (Sebastes spp), or Tilapia, which accounted for over half the “snapper” sold in sushi restaurants. All “snapper” samples from Washington, DC, were mislabeled.

A primary source of mislabeled tuna were Sushi restaurants, where 71% of “tuna” was mislabeled. The name “White tuna” can only be applied to Albacore Thunnus alalunga, but almost all (94%) of “white tuna” was mislabeled; 84% of this was actually Escolar (Lepidocybium flavobrunneum), a type of snake mackerel. Escolar is a common bycatch species known as “butterfish” in Hawaii, that contains a toxin that often produces gastrointestinal distress when consumed. One of the least commonly mislabeled fish was salmon, with only 7% mislabeled, and mislabeling was less common in grocery stores than in restaurants, where farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) was often mislabeled as wild Alaskan salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.). In some cases, low value species (Pink, Chum) were sold as high value species (Chinook/king or Silver/Coho). The rate of mis-labeling for salmon was much greater in winter, when fish were out of season, than in summer, when fresh fish were available.

Some Fishy Tails

One of the tastiest fish in the sea (IMHO) is blackcod, or sablefish, Anoplopoma fimbria. These are caught by longline fisheries that also target halibut in the Pacific Northwest, primarily Alaska and British Columbia. In Canada, sablefish are sometimes referred to as “butterfish”. This is confusing because Oceana found that all samples labeled butterfish were actually Escolar. In the US, “butterfish” usually refers to Peprilus triacanthus, a small, oily fish caught by trawls and often smoked.

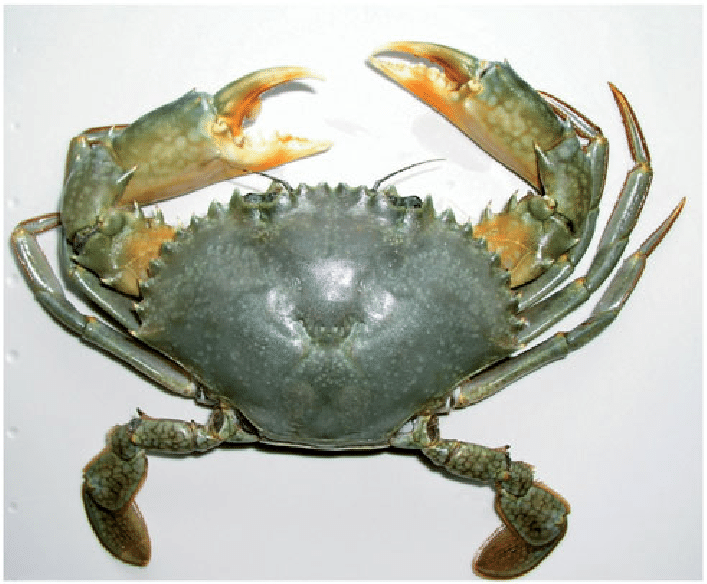

Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus, is an iconic species of the Chesapeake Bay and Maryland. But as populations have fluctuated recently, many restaurants have started to import other types of crabs, which are usually a lower value species. The biggest crab fishery in the world is that for blue swimmer crabs Portunus pelagicus, which are imported from China and other Southeast Asian countries, usually as canned crabmeat. This is commonly used for crabcakes in restaurants. Another study by Oceana found that 48% of crab cakes sampled in Maryland contained other species of crab from Southeast Asia or Mexico. In Baltimore and Annapolis, the principalis locus of blue crab gastronomy, and two places that should know better, 46-47% of crab cakes contained meat from other crab species. Ocean City and Washington, DC, came in second place, with 38% of crab cakes mislabeled. Towns on the Eastern Shore (Cambridge, Easton, St. Michaels), where the crabs are actually caught, had the least amount of mislabeling (9%). If the menu doesn’t specify, and if you don’t ask, your crab cakes are most likely made from blue swimmer crab. Unlike Maryland blue crabs, which are caught with traps or trotlines that have little bycatch, up to half of the imported crab comes from non-sustainable fisheries with high bycatch, or illegal/unregulated/unreported fisheries (IUU). Another popular way to eat blue crab is as softshell crab. But even that is often substituted with Southeast Asian mud crab Scylla serrata, from the Philippines and Indonesia. These are usually captured as wild juveniles, then raised in muddy pens or ponds and fed animal scraps.

If you ever see a label on wild seafood that says “Organic”, don’t believe it. There is no such thing. That’s because the Organic standard requires complete control over production, including all inputs (feeds, supplements, etc). But we can’t control what wild fish eat. Furthermore, there are no USDA standards for farmed seafoods. But aquaculture products can be labeled as Organic, including Tilapia.

Why and how does mislabeling occur?

Not surprisingly, most seafood mislabeling occurs due to financial incentives. The most desirable seafoods are often expensive, and sometimes rare, whereas alternative species may be cheaper and more plentiful. They may also be less sustainable. Many of the species substituted are bycatch species of lower value that may not have any direct market (e.g. Escolar). Another reason may be language issues, e.g. in the sushi trade. Hamachi, a common sushi staple, is often called yellowtail, but it is not yellowtail tuna; rather it is a type of amberjack. Fish caught in a mixed species fishery, e.g. rockfish (Sebastes), are often filleted on board, and can’t be identified correctly by the time they return to port.

Seafood substitutions not only defraud the consumer, but create unfair competition, depriving fishers and processors of income. Mislabeling can also lead to health concerns. Farmed fish are often less healthful due to the administration of hormones or antibiotics. Some may have toxins (e.g. Escolar); many reef fish contain ciguatera (fish poisoning), which is produced by microalgae and concentrated up the food chain.

“One name for one fish” (ONFOF)

The best way to defeat seafood mislabeling is to require species-specific names for all seafoods. According to Oceana,

“One simple but vital step the federal government can take is requiring the use of species-specific names, or one name for one fish, throughout the seafood supply chain, from the fishing boat to the dinner plate.”

The best and most unique name is the Latin or scientific name. Since most people couldn’t remember or pronounce them, the second best name is the AFS-approved common name. Single-name labeling is required in the EU, but not in US. ONFOF is the best way to prevent fish fraud and illegal fishing. It would help track seafood through the supply chain, prevent IUU fishing, and protect vulnerable species. It would also help consumers make choices that are healthy and sustainable.

What can you do?

As a consumer, you can reduce the risk of seafood fraud in several ways. If possible, buy whole fish, so you can see what it is before filleting. Check the price; is it too good to be true? If so, it may have been substituted with a lower-value species. In the store or restaurant, ask questions. If the server doesn’t know the answer, have them ask the manager or chef. Questions you should ask include:

What species is this? Or at least which of the multiple types of snapper, grouper, or salmon is it?

Where is it from? What country, region, or general location?

Is it wild or farmed?

Is it certified as sustainable?

The best way to get good seafood is to be an informed consumer. Knowing what you are eating will help you get tasteful and healthy meals that do not contribute to overfishing or conservation problems. Buying correctly labeled fish supports honest fishers, processors, and retailers, and contributes to the well-being of fishing communities. There shouldn’t be anything fishy about fresh fish.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

[1] Nelson J. S. et al., eds. 2004. Common and scientific names of fishes from the United States, Canada and Mexico. American Fisheries Society Special Publication 29. Bethesda, MD. 386 pp.

[2] C. P. Balasubramanian, S. Cubelio, D. L. Mohanlal, A. G. Ponniah, R. Kumar, K.K. Bineesh, R. Pitchaiyappan, D.R. Gopalakrishnan, A. Mandal, and J.K. Jena (2014). DNA sequence information resolves taxonomic ambiguity of the common mud crab species (Genus Scylla ) in Indian waters. Mitochondrial DNA. 27. 10.3109/19401736.2014.892076.

Bradley, this was a really interesting article. I learned a lot. I live where fresh fish is not common so frequently order it when I travel. This will definitely help me make better choices.