Sustainable Seafood 5: Seafood Contamination

In which the E@L dishes the dirt on mercury, chemicals, plastics, and pathogens

As dedicated readers know by now, eating seafood is an important part of a healthy diet and provides a low-fat, low-calorie source of protein. But you should also be aware that seafood, like all foods, can contain harmful contaminants, including heavy metals, microplastics, harmful chemicals, and pathogens. Knowledge about the presence of these in different seafoods, however, can help you make safe, healthy choices about what to eat.

Mercury

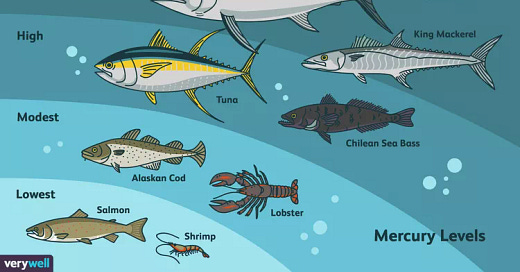

All seafood contains mercury (Hg), which is a potent neurotoxin. Most of it is derived from natural, terrestrial sources and is picked up through the food chain. As a result, organisms at the bottom of the food chain, such as plankton, have the lowest concentrations, and apex predators at the top of the food chain have the highest concentrations. As a rule of thumb, the bigger the fish, the higher the concentration. This happens due to biomagnification; larger animals eat smaller ones, but don’t rid themselves of the contaminants, which accumulate in their bodies. Larger fish also live longer, so have more time to accumulate contaminants.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) conducted a 22 year study on mercury contamination in fish and shellfish. The FDA study showed that herbivores and detritivores such as bivalves (oysters, clams, scallops) and filter feeders like shrimp had the lowest levels of mercury (<0.01 parts per million, ppm), so are good choices to eat. At the next trophic level, planktivores such as forage fish (sardines, anchovies, shad, herring), omnivorous fish (salmon, pollock, flounders, mackerel), and some crustaceans (crayfish, crabs, and lobster) had levels ranging from 0.01 to 0.10 ppm. These are still low enough that they are considered safe to eat. Highly piscivorous fish, though, had levels ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 ppm; this group includes cod, perch, tuna, tilefish, monkfish, snapper, bass, and halibut. At this level, we should start to be careful about how much we eat. Fish at the highest level of the food chain had levels that we should really be concerned about, ranging from 0.3 to over 1.0 ppm. This group includes larger tuna (e.g. bigeye and bluefin), shark, swordfish, sablefish, bluefish, grouper, King mackerel, marlin, orange roughy, and tilefish. These seafoods should only be eaten sparingly.

How much seafood is safe to eat?

Eating seafood is extremely beneficial for cardiovascular health, and reduces the risks of cancer and other sources of mortality. So, although we should be concerned about mercury contamination, the benefits of eating seafood outweigh the harmful effects from low levels of mercury. The beneficial effect becomes most apparent for those who eat 2-4 servings of seafood per week. We should, however, limit the amount of certain seafoods that we eat. And certain demographics are more sensitive than others. Pregnant women, for example, should stick to only the safest choices. Children should not eat more than 1 ounce per meal for each 3 years of age (rounded up), up to age 12, after which they can eat adult portions. Older people with underlying health conditions such as heart disease should limit their exposure to seafood. And people who normally eat a lot of seafood (myself included) should also watch their intake.

Canned tuna is one of the most popular seafood items for both adults and children, but some is safer than others. Among tunas, the bigger species have more mercury, so Bigeye tuna would have more than Albacore, which would have more than skipjack. You can safely eat up to three 5-oz cans of skipjack (“light”) tuna per week. But you should not eat more than one can per week of albacore tuna. Children should eat less than this, and pregnant women should not eat any canned tuna.

Other Contaminants

Polyflourinated alkenes (PFAs) are some of the so-called forever chemicals that never degrade. They originate from industrial sources, including fire retardants, and can have detrimental health effects. Exposure to some types of PFAs can cause developmental defects, changes to liver function, reduced immune response and certain kinds of cancer. The presence of PFAs is most common in seafoods from industrial areas, especially in urban areas, freshwater lakes, and rivers, and is not related to fish size. One of the highest sources of PFAs was in canned clams from China, according to another study by the FDA , who recommended not eating more than 10 oz per month. Fish that may have high levels of PFAs include catfish, bass, and perch, so should be more of a concern for recreational fishers. PFAs are uncommon in ocean fish (cod, pollock, tuna). In contrast to mercury contamination, though, lobster and shrimp had relatively high levels of PFAs.

For recreational fishermen who want to eat their catch, some states provide local advisories about seafood contamination. In Maryland, where I live, an interactive map provides information about specific contaminants in fish from different water bodies, and how much is recommended to eat.

Plastics in Seafood

Plastics in food can take two forms, physical (micro- and nano-plastics) and chemical plasticizers (Phthalates). Consumer Reports published a study of plastics in food in their issue of February 2024. Their article provided information on micrograms (µg of phthalates per “serving” but did not define the size of a serving (we’re assuming it is about 100 grams, or about 3.5 ounces). The highest levels in seafood (24.3 µg) occurred in canned pink salmon. Sardines in oil contained 7.8 µg; chopped clams 4.4 µg; Light Tuna in water 1.7 µg. How much is safe? Not enough research has been done to answer the question, but less is definitely better.

A joint study by the University of Toronto and the Ocean Conservancy tested for the presence of microplastics in sixteen types of protein sources, and found microplastics in 88% of 111 individual samples tested. Microplastics (MPs) found included fibers, plastic particles, and rubber fragments, and ranged in size from 0.04 to 27 mm. Minimally processed foods such as chicken breasts, Pollock fillets and fresh white Gulf shrimp had the least amount of MPs (<0.1 particle per gram), whereas highly processed foods made from those same sources, such as fish sticks (0.26), chicken nuggets (0.31), and breaded shrimp (1.2) had the highest levels of MPs. Nanoplastics and microfibers have been found in virtually every habitat on earth and every type of organism tested, including many parts of the human body. When ingested, microplastics can cause inflammation or physical harm by damaging our respiratory and intestinal tracts. Toxicity can be caused by the chemical compounds themselves, by contaminants, or by additives (catalysts, lubricants, dyes, plasticizers, etc).

It is not clear why breaded products have more microplastics, nor whether the source is in the breading or the food processing machinery. The E@L recommends avoiding any factory-breaded seafood products. In a restaurant setting, I only eat breaded seafood that has been prepared on-site.

Pathogens and Parasites

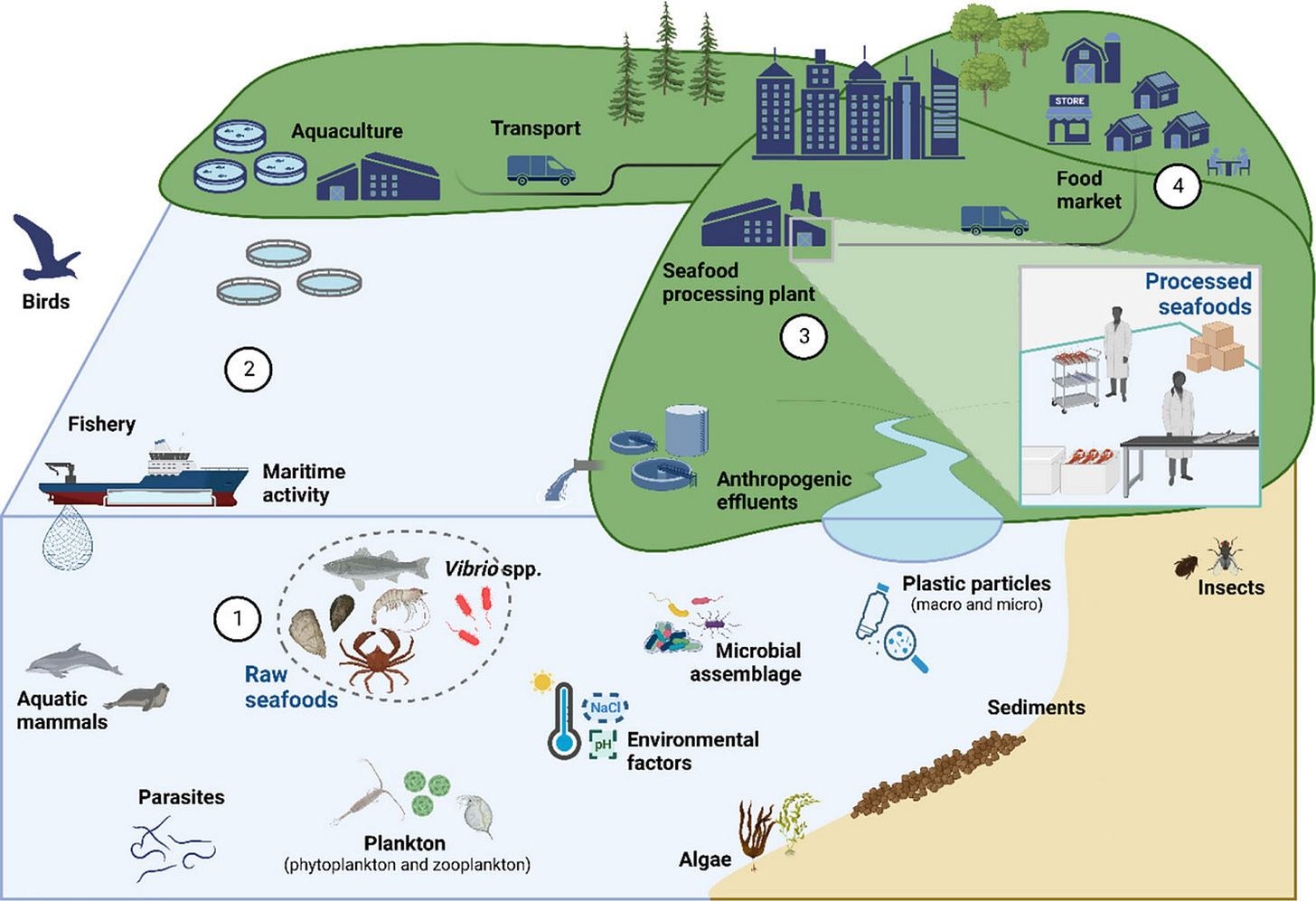

Bacteria are present on all types of raw meat, including fish. Pathogens associated with fish can include Vibrio, Salmonella, Listeria, Shigella, Aeromonas and others1, some of which can cause symptoms of food poisoning such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea 2. Pathogens may occur in wild or cultivated seafood, and may be introduced from the water where the fish was caught or raised, during processing, or via cross-contamination from humans or other sources. Vibrio species occur naturally in seawater but may be more highly concentrated near sources of urban pollution, especially untreated wastewater 2. Aquaculture operations also promote Vibrio infestations because tanks and ponds may act as reservoirs, and the high density of animals promotes transmission. Furthermore, introduction of antibiotics in feeds promotes development of antibiotic resistant strains. Cultivated fish such as Tilapia, European sea bass (aka branzino, bar, or loup de mer), and shrimp grown in ponds or tanks are particularly susceptible2. Vibrio may form stable films on processing equipment that are difficult to clean and may contaminate other seafood products, thus ending up in the retail marketplace. While the muscle tissue is generally sterile, fish guts, gills, and skin often carry bacteria that may be transferred to the flesh during processing3. Vibrio can also attach to plastic microparticles, which then become vectors for pathogen transmission to humans and fish. Seafood may also be contaminated by bird droppings in aquaculture or processing areas. Increased water temperature promotes the prevalence of Vibrio, so it is of greater concern during warmer months and in areas where climate change has caused increased water temperature. Listeria monocytogenes is another common pathogen in seafood and causes listeriosis, which is uncommon, but may cause high mortality in immuno-compromised individuals 3. Salmonella may also be found on seafood and is more common in filter feeders such as bivalves and shrimp because they concentrate it during feeding.

Cooking to 145°F kills most pathogens, so pathogens are mostly of concern when eating raw fish such as sushi. Generally speaking, fresh fish should smell like the ocean. The “fishy” smell of spoiled fish is due to the presence of ammonia produced by bacteria, so if it smells, don’t eat it. Some fish, such as cod and salmon, carry parasites such as roundworms or tapeworms, which are transmitted by consumption to their final host, warm-blooded marine mammals. These are usually killed by cooking or by deep freezing, as done prior to making sushi. Shellfish typically do not carry any parasites that can infect humans, but they may carry bacteria, esp Vibrio species, which can lead to diarrhea and vomiting. A severe outbreak of Vibriosis that occurred in the United States in 2018 was linked to crab meat from Venezuelan processors 2.

Eat Fresh, Eat Safe

As a general rule, fresh seafood is safe to eat for a few days to a week. When buying bivalves such as clams and oysters, only accept those with closed shells. Open shells indicate that they are dead and may be breeding bacteria. Any fish that smells “fishy” or is exceptionally slimy should be avoided. And you can limit your exposure to mercury and other contaminants by being aware of which fish are likely to have higher concentrations and eating less of them. Following a few simple guidelines can help you enjoy safe, high quality seafood year-round.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

Additional Sources for this Article:

1 Afreen, Maliha, and İlknur Bağdatlı. 2021. "Food-borne pathogens in seafood." Eurasian Journal of Agricultural Research 5.1: 44-58.

2 Brauge, T., Mougin, J., Ells, T., & Midelet, G. 2024. Sources and contamination routes of seafood with human pathogenic Vibrio spp.: A Farm-to-Fork approach. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 23, e13283. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.13283

3 Novoslavskij, A., Terentjeva, M., Eizenberga, I. et al. 2016. Major foodborne pathogens in fish and fish products: a review. Ann Microbiol 66:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-015-1102-5

Good morning Brad. Thank you for your informative articles, which I read with interest. In this one, in the section on “Pathogens and Parasites “, I was concerned that you did not address directly, how riddled with both pathogens and parasites farmed Salmon are, besides how destructive the pollution from open net Fish Farms are to the ocean environment. As widespread as salmon farming is, from New Zealand to South America, Canada and the British Isles, and throughout Scandinavia, the impact is massive, and consumption of the toxic product, farmed salmon, is huge and widespread, so I was surprised you did not address their serious levels of both pathogens and parasites. In view of your long tenure in an Alaskan commercial fishing environment, you surely are aware.

However, you may wish to read “Not on My Watch” by Alexandra Morton.

My best to you and your family, from ours in the PNW.