# 25-14 The Incredible Edible Oyster, Part 2: Oyster Wars and and Molluscan Millionaires

In which the E@L tells tales of Outlaw Dredgers, Pirate Fishermen, and the Oyster Navy

Why then the world’s mine oyster, Which I with sword will open. – William Shakespeare

Most people misinterpret that line to imply that the speaker has gained a valuable bounty, when in fact the speaker is actually threatening to use force to take advantage of others. It has nothing at all to do with oysters, or bounty. It as all to do with our story, however.

But oysters were once bountiful. Oysters have been harvested for food in Europe and Asia since neolithic times. Ancient Romans considered them delicacies and used the shells for construction materials. Native Americans used oysters for food, and to make tools, weapons, and decorations. They ate both raw and smoked oysters, leaving behind shell middens many acres in size. Early European settlers in America saw oysters as an important food source, and considered them an unlimited natural resource, which led to rapid overharvesting, and eventually, war on the water.

1. Tongs and Canoes

Early fishermen were mostly farmers who collected oysters with tongs in shallow water during the off season (winter). Tongers operated from small boats, essentially canoes made from logs, with a mast and sail. Tongs consist of a pair of handles up to 20 feet long with claws on the ends; they were originally operated by hand, though modern versions are hydraulic (patent tongs). Tongers stood in their boats, lowered the tongs to the bottom and worked them back and forth until they felt oysters in their grip, then lifted the heavy mass up into their boat, where another man sorted the oysters and discarded the small ones (culls).

The “watermen” thought that oysters were inexhaustible. In New England, oysters were harvested by dragging a dredge with iron teeth across the oyster beds, breaking off clumps of oysters that could be hauled up by the bushel. By the early 1800’s, dredging had depleted oysters from Maine to New York. Dredgers then moved down to Delaware and Chesapeake Bays where they found an even larger source.

2. Oyster Drudgery

The “drudgers”, as they were known, competed intensely with local tongers, leading Maryland to ban oyster dredging by non-residents. Packing houses sprung up in Baltimore, where they lined the bayfront, buying oysters from all over Chesapeake Bay. By 1860, the Baltimore & Ohio railway was shipping oysters over the mountains to the Midwest. Oystering suffered a recession during the Civil War, during which watermen became smugglers to earn their living. After the war, development of steam canning allowed oysters to be preserved, and expanded the markets all the way to the gold fields of Colorado and California. Demand for oysters rapidly exceeded the supply available and led to greater development of the industry.

John Crisfield was an early oyster speculator who invested in the Eastern Shore Railroad, bringing tracks to the little village of Crisfield, Maryland, on Tangier Sound, which soon became the center of the Chesapeake Bay oyster industry. Over 600 boats worked out of Crisfield, sending trainloads of oysters to Philadelphia daily. The town of Crisfield was literally built atop acres of oyster shells, which ultimately deprived the oysters of valuable habitat for spat settlement. John Crisfied was one of the first, but not the last, to make millions from mining molluscs.

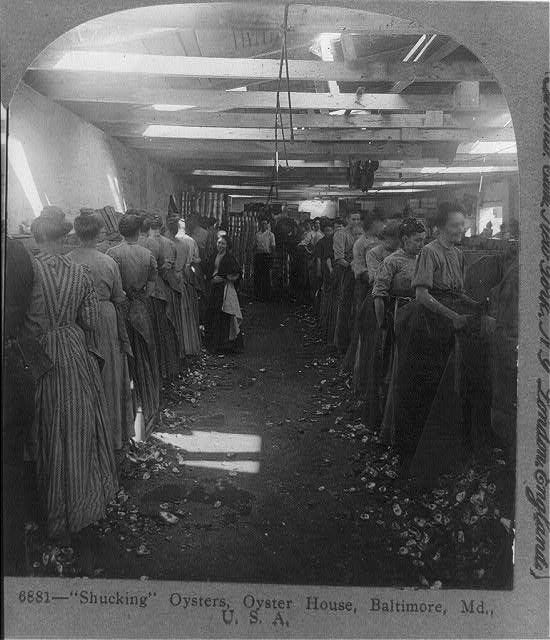

The demand for skilled watermen and oyster shuckers in the Eastern Shore towns of Crisfield, Cambridge, Oxford, and St. Michaels was such that they welcomed itinerant black workers, who soon became pillars of the community. While this may have annoyed the “cultured” elites of the area, racism and Jim Crow had no place along the bustling waterfront of the oyster towns or among the hard-working crews of oyster boats. Oystering was one of the few occupations in which black workers were as valued and respected as whites.

But it was a hard life. Tonging the oysters and lifting them up from the depths was physically demanding work. Watermen worked during the wet, cold winter months, and many suffered from injuries, rheumatism, arthritis, and Tuberculosis. Their major focus was surviving the winter, and when back on shore, lived life to the fullest in the local bars.

3. The Wild Eastern Shore

The Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virgina was a vast wetland of untamed marsh, creeks, and islands. The marshes supported millions of birds, baby crabs and fish, terrapins, muskrats, deer, and other wildlife. The marshes and nearby oyster reefs protected the shoreline from storms and erosion as well as from human settlement. Whereas inland areas attracted farmers and settlers, the marshy shorelands attracted drifters, escaped slaves, miscreants, and other undesirables who hid among the maze-like channels. Many of these people were crude and lawless and had little use for civilized life. They became watermen instead. The oyster towns that they founded were crude places that rivaled the Wild West in their rough and tumble lifestyle.

The Eastern Shore towns of Onancock, Crisfield, Pokomoke (then Newtown), Whitehaven, Cambridge, Oxford, Easton, and Chestertown were all built around the business of oystering. In Maryland, over 32,000 people were employed directly in the oyster business. Packing houses lined the waterfronts, employing over 500 shuckers in Cambridge alone, most of whom were women. Chesapeake Bay provided over 40% of the world’s oyster production.

Over time, Chesapeake Bay watermen developed a unique type of boat, the oyster Skipjack, that could harvest oysters by dragging a dredge under sail in deep water. In the 1880s, over a thousand boats fished for oysters in Chesapeake Bay, landing over 150 million bushels per year. But landings declined rapidly as all the oyster “bars” were found and harvested. In 1865, legislation restricted oystering to tonging from small boats in the shallow creeks or dredging under sail in deeper waters. But “drudgers” began seeking oysters in the shallow rivers and creeks and competing directly with tongers. The Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia became a lawless place full of outlaw oystermen. The situation was akin to the California gold rush, but instead of mining gold, watermen were mining oysters.

4. Slavery at Sea

The 1880s were the epitome of oyster exploitation. Over 15 million bushels of oysters, weighing about 125 million pounds, were being harvested annually. A shortage of oysters in Europe drove prices to over $30 a bushel. Boats needed ten or twelve men each to operate the hand-cranked dredge winches and crew were in short supply. To meet their needs, boat captains shanghaied or kidnapped men from bars in Baltimore and put them to work on dredge boats for months at a time. Newly arrived immigrants from Germany, Italy, and Ireland, called “Paddies” were met at Ellis Island by Contractors who offered them contracts for work, and shipped them directly to boats in Baltimore.

Well after the Civil War, another kind of slavery persisted aboard the oyster boats. Most of the Paddies were treated horribly, worked in terrible conditions, and were paid poorly if at all. They were not permitted ashore, lest they escape. Some oystermen were killed by their skippers, and some skippers by their crews. Rather than pay the crew, some skippers simply had them knocked overboard (“Paid off by the boom”) and left to drown. Legislators turned a blind eye because they were beholden to wealthy oyster packers. Eventually, immigrant rights groups forced through a law requiring dredge captains to register and be responsible for all the men working aboard their vessels.

This situation persisted until about 1907, when a new invention came along. The gas-engine powered windlass could do the work of four men, replacing the manpower previously required, and reducing the need for crew. Instead of needing ten or twelve men, now a dredge boat could operate with five or six. Rather than being just muscle, watermen became a team of experienced and valuable professionals.

5. The Oyster Wars

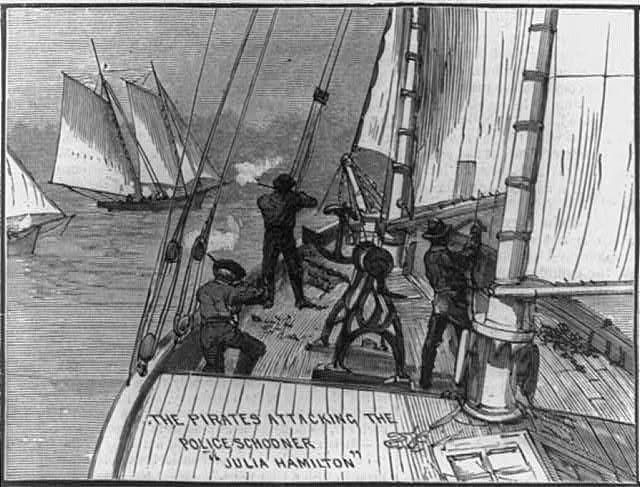

The conflict began when dredgers started to invade the shallow creeks that were restricted to tongers. Violence erupted when the tongers fired shots at dredgers and some watermen turned up dead. Pirate oystermen often fished at night, in fleets of skipjacks. In 1868, Maryland created the Oyster Navy to enforce the law limiting dredgers to deeper waters within their own counties. Although the Navy had some dedicated schooners and at least one steam vessel with a mounted howitzer, they were underfunded, outnumbered, and outgunned by the pirates. Nonetheless, the Oyster Navy arrested and fined those who fished illegally and killed several watermen fleeing arrest. By 1872, police boats were stationed on every major oyster river, but they were not popular and were occasionally attacked by watermen.

In Cambridge, Maryland, a group of pirates overwhelmed a Navy schooner and took the policemen prisoner, forcing them to work aboard the dredges for three days before releasing them. Meanwhile, the town of Cambridge organized its own militia to protect Choptank river oysters from predation by pirates, who responded by threatening to burn down the town. Despite pleas for assistance, the State of Maryland refused to send in the Oyster Police, who were busy fighting piracy elsewhere.

In the 1880’s, the Chester River became the center of oyster piracy. Dredgers fortified their boats with steel plates so they could operate even while being fired upon. One moonless night in December, 1888, the Oyster Police steamer Governor McLane, under command of Capt. C. B. Howard, cruised slowly into the Chester River where over 70 boats were dredging illegally. In the darkness, police rowed a boat up to a dredger, boarded it and arrested the crew. After a second boat was boarded, the dredgers rafted together a dozen armored boats and began shooting at the Mclane. In response, Capt. Howard rammed the Mclane into two of the dredge boats, sinking them. Unknown to the policemen, both vessels held captive crew members in their holds, who went down with the boats.

By 1884, most of the Oyster Navy sailors were political appointees who lacked both the enthusiasm for the job and the skills to do it. They had little to no training in either police work or seamanship, and could not sail or fight as well as the oystermen, so they basically gave up trying to enforce the law. The conflict came to a head when a group of pirates mistook a passenger steamship for an Oyster Navy boat and fired hundreds of bullets into it. The outraged citizenry of Maryland demanded that their legislators stop the piracy and pillaging, which led to increased funding for the Oyster Navy. But the oystermen defied the rules until the Oyster Navy was sent in and began arresting and fining the scofflaws.

6. Go Westward, Young Pirate

In 1889, Virginia began allowing private leasing of barren grounds for oystering. Watermen seeded them with shell to attract new spat settlement, then harvested them at will. One such location was Hog Island, near the mouth of the Potomac River. Maryland watermen did not recognize the rights of Virginia watermen to Hog Island or most of Pocomoke Sound on the Eastern Shore. Adding to the conflict, Virginia watermen poached on Maryland oyster bars at night. At the time, there was no legitimate boundary between the two states, and both claimed major portions of Tangier and Pocomoke sounds, the richest oyster grounds in Chesapeake Bay.

A Virginia waterman named Charles Lewis owned an oyster lease on Hog Island. In November 1889, one of his boats rammed a boat from Smith Island, Maryland, owned by George Evans that was dredging on Lewis's lease, taking Evans and his crew aboard as his boat sank. They were released in Crisfield, MD, with a warning to stay away from Hog Island. But later that month Evans and his crew returned, and opened fire on Virginia boats that tried to chase them off. That winter, over a dozen men were killed at Hog Island. As watermen fought over these grounds, neither the Maryland nor Virginia Oyster Police offered to intervene, so watermen did their job, firing on boats that entered “their” waters.

Improvements in boats, engines, fishing gear, and processing technology, as well as increased demand are the drivers that cause the downward spiral of all fisheries, and oysters were a textbook case. Between 1884 and 1890, oyster harvests fell from 15 million bushels to 10 million bushels.

As the oyster beds of the Eastern Shore became exhausted, watermen from those areas began moving westward across the bay into the Potomac River. But the border between Maryland and Virginia was still in dispute. The entire Potomac River was under jurisdiction of Maryland, right up to the Virginia shoreline, but the Compact of 1785 gave both states the rights to harvest oysters from the river. The encroaching Eastern Shore watermen were compared to Vikings invading Britain. They raided property in St. Mary's County, stealing chickens, pigs, and sheep, and pillaged the general store, causing locals to start shooting at any dredgers approaching shore.

The depression and WWII caused a decline in oystering as prices collapsed to 15 cents a bushel, and many boats and watermen were incorporated into the war effort. But things heated up again after the war as prices rose to 45 cents a bushel. Colonial Beach, VA, just 70 miles downriver from Washington, DC, became the center of postwar oyster piracy. A “mosquito fleet” developed, consisting of fast boats with powerful outboard engines that dredged at night. Virginia watermen enjoyed the game of “cops and robbers” and delighted in running circles around the Maryland Police boats. Maryland responded by outfitting WWII surplus PT boats with water-cooled machine guns. They sank a few boats and confiscated others, but mostly just chased the rest away, making pirate oystering more difficult.

Conflicts with the Maryland Police led to the deaths of several prominent Virginia watermen. The resulting outcry prompted Maryland to clean up the ranks of its Navy and impose strict requirements for training in police work and community relations. In 1957, the Maryland legislature took complete control of Potomac River fisheries, which caused outrage in Virginia. Eventually, the States came to an agreement, establishing the Potomac River Fisheries Commission in 1962, that would jointly regulate the Potomac River, conduct seafood inspections, and promote scientific research.

7. The Beginning of the End

In 1878, the first scientific study of the Maryland oyster bars was conducted by a US Navy Officer, at the request of the Maryland legislature. The results showed that oyster populations were declining due to the overharvest of young oysters, and failure to replenish the beds with oyster shells. But watermen were making too much money to be concerned about conservation.

One of the major problems caused by the Oyster Rush was that removing millions of tons of oyster shells from Chesapeake Bay had depleted the available habitat for small oysters. This was made worse by the lack of legislation regulating the fishery. Watermen started to keep juvenile oysters smaller than 3 inches, depriving oyster populations of future adults.

In 1892, Dr. William K. Brooks, a professor at John's Hopkins University, was the world's expert on oyster biology and fisheries and published a book on the subject. He warned the Maryland Legislature that:

“The oyster laws are not enforced and the Bay is losing its young oysters. Soon there will be none left to replenish the beds. Unless prompt and decisive action is taken, the Chesapeake will go into serious decline”.

He also stated:

"It is a well-known fact that our public beds have been brought to the verge of ruin by the men who fish them,… all who are familiar with the subject have long been aware that our present system can have only one result – extermination. ….the residents supposed that their natural beds were inexhaustible until they suddenly found that they were exhausted."

As oysters became scarce, more were transplanted from Virginia, North and South Carolina, Florida, and Texas. In the 1950s these transplants introduced various predators, such as the oyster drill, and two diseases, called Dermo and MSX, which contributed to further declines. Because public reefs were overfished, Virginia allowed oystermen to plant oysters on over 110,000 acres of leased barren subtidal grounds. By 1965 these were providing >95% of the oysters in Chesapeake Bay. Seeding oysters on leased ground increases harvests and spat production and reduces the pressure on public oyster bars.

Maryland watermen, though, opposed the idea of cultivating oysters on leased grounds. They considered it to be “Privatization of a public resource”, and they wanted “protection of ancient privileges" and "common law rights". These are typical arguments used to oppose improved fishery management. As described in an earlier post, open-access fisheries for many other species, justified as “Freedom of the Seas”, typically led to the Tragedy of the Commons, in which everyone competed for a limited resource and no one took responsibility for it. Giving harvesters certain rights (to locations or amounts) guarantees their production and alleviates the competitive pressure. Eventually, Maryland allowed leasing of public grounds but hamstrung their own efforts by prohibiting watermen from harvesting them with dredges or buying seed from Maryland suppliers. As of 2025, there were 430 private leases in Maryland covering 7000 acres, and producing 75,000 bushels of oysters per year.

Despite these efforts, Chesapeake Bay oyster harvests continued to decline due to over-harvesting, habitat destruction, disease, pollution, excess agricultural fertilizer causing phytoplankton blooms, siltation and smothering of spat, reduced light penetration, and loss of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). By 2000, harvests were less than 1 million bushels, and the eastern oyster was being considered for the endangered species list.

We pause our story at this low point in history, but rest assured, dear reader, there is good news in the next episode as we show how aquaculture has rebuilt the oyster industry and helped to restore depleted reefs.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

Sources

Kurlansky, M. (2006) The Big Oyster. History on the Half Shell. Ballantine Books. New York, NY. 307 pp.

Wennersten, J. R. (1986) The Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay. Tidewater Publishers, Centreville, MD. 147 pp.

Great post.

We've got a lot of Oyster Fishermen here on Louisiana's Gulf Coast. Their catch is in decline, and it's funny how no one wants to listen to them as the fossil fuel industry and climate change are destroy the habitats they rely on. They're the trip wire, and they're the experts, but they have no clout and no voice.

We're trying to do something about it: https://open.substack.com/pub/habitatrecoveryproject/p/the-environmental-truth-caught-in?r=52vkqq&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true