Sustainable Seafood 9. Farmed Atlantic Salmon

In which the E@L explores the controversies around salmon aquaculture

Describing five species of Pacific salmon in the previous segment required summarizing an immense amount of information. My goal, however, was not to overwhelm you with details, but to help you distinguish the differences in flavor, quality, and value between the different salmon species. In this section, my strict focus on Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar may therefore seem like unequal treatment. My reasons for doing so, though, are first, that more people have consumed, and are familiar with, farmed Atlantic salmon than wild salmon, and second, that the ramifications of aquaculture are little known, but have widespread impacts on the environment, wild fish, nutrition, food safety, economics, social systems and other aspects of human interest.

Virtually all Atlantic salmon on the market are farmed, and virtually all farmed salmon are Atlantic salmon. There are some farmed coho and chinook salmon on the market but, as a generality, farmed salmon are equivalent to Atlantic salmon. Atlantic salmon are the only species of salmon native to the Atlantic Ocean. At one time they were abundant in streams around Northern Europe and Russia, particularly Norway, Scotland, and England. In the Western Atlantic, they were abundant from Greenland, through Labrador, and south through New England. Most of the wild stocks are no longer viable, due to habitat destruction, forest removal, development, dam construction, and overfishing. The only wild populations remaining in the United States reside in a few rivers in Maine and are considered endangered.

Like Pacific salmon, Atlantic salmon spawn in freshwater streams. After hatching, the juveniles spend two years in freshwater, then go to sea, and may migrate from Maine all the way to Newfoundland, Labrador, and Greenland. After two (or sometimes only one) years at sea, they return to spawn in freshwater as adults weighing 8-12 lbs. Unlike Pacific salmon, Atlantic salmon do not die immediately, but may go back out to sea, then return to freshwater and spawn again the following year.

Atlantic Salmon Farming

There are no commercial or recreational fisheries for wild salmon in the United States or Canada. Therefore, there is no such thing as “wild Atlantic salmon” on the market, and anything marketed as such would be fraudulent. All Atlantic salmon encountered in the marketplace are farmed. Salmon farming is a major business around the world, wherever there is access to clean, cold seawater. Norway and Scotland are the two major sources, followed by Chile and Canada. Salmon farming is one of the most rapidly growing methods of food production in the world. As a result, we now eat three times more salmon than we did in 1980.

Typically, adult salmon are spawned in land-based pens, and the eggs and fry retained in a hatchery until they are large enough to live in saltwater. At that time, they are transferred to large net pens, either round or square, often placed in deep, fjord-like inlets where there is good water exchange. Pens may range from 10 to 100 meters in size and contain 10,000 to 200,000 fish. Fish may also be raised to market size in indoor tanks, where wastewater is treated before disposal. This is a more sustainable method because it avoids many of the pitfalls of net pen cultivation (see below).

The fish are fed pelleted food that is a mixture of mostly other fish plus vitamins. Their food also contains astaxanthin, a natural carotenoid that gives the red color to their flesh. Such fish are often labeled with “Dye added” but that does not mean the fish was injected with red dye #4. Wild fish normally acquire astaxanthin from the small crustaceans they consume, but it must be added to the feed of cultivated fish. Antibiotics may also be introduced into the feed.

Is There Another way?

Raising fish in enclosed nets creates a number of environmental and sustainability problems, which are detailed below. Raising fish in completely enclosed indoor tanks, called recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), however, solves some of those problems. Waste products are contained, sterilized, and either eliminated by biochemical decomposition or trucked off to landfills. No fish can escape from the systems, so interbreeding and disease/parasite transmission is prevented.

The one remaining problem is that of taste – fish raised in tanks produce compounds collectively called geosmin, which creates a moldy, earthy, muddy flavor. The only way, currently, to eliminate it is to move the fish to tanks with clean water and not feed them for 3-5 days prior to harvest, allowing them to purge the off-flavors from the fish flesh. Then, the purge water is released, or dumped, into natural streams. This may not be an issue if the purge water volume is small relative to streamflow. But in some cases it may be a large proportion.

As it turns out, land-based farming of salmon has yet to become practical or economical due to a number of obstacles. As a case in point, in 2022, a company named Aquacon Maryland LLC planned to build a large salmon production facility in Federalsburg, Maryland. Aquacon proposed to produce 100,000 lbs of fish per day, and release 2 million gallons of purge-water into Marshyhope Creek daily. During fall and winter, when rainfall was high, that would only amount to a few percent of total streamflow, but during low-water seasons it amounted to a significant portion of normal flow.

In the fall of 2022, a group of local citizens, and scientists from the University of Maryland (your E@L included), met with the Federalsburg Town Council, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and Aquacon principals to protest the facility construction. Dr. David Secor, of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, told the group that Marshyhope Creek was the only freshwater body in Maryland that still supported a spawning population of sturgeon, and that any contamination or disturbance of waterflow in the creek would be “an existential threat” to the sturgeon. Spokesmen for Aquacon admitted that purging of geosmin was a problem, and they hoped to be able to eliminate that step in a few years. As a result of this meeting, and subsequent talks, Aquacon later retracted their request for a permit, and facility construction was ultimately cancelled.

Problems with Salmon Aquaculture

Salmon farming presents a number of environmental, ethical, and sustainability issues, including the following:

Nutrient Overload. High densities of fish in a net pen produce a lot of nutrients in the form of excess feed and feces. Most of this drops into the water column and settles to the seafloor below. These excess nutrients can cause benthic eutrophication and disruption of the local marine ecosystem, reducing oxygen concentration and benthic diversity. This can be prevented if pens are sited properly, in deep enough water where flushing is strong, so the waste products will be carried away. Future fish farms may recycle these nutrients by using polyculture systems that include algae or mussels cultured beneath the fish pens.

RAS Wastes. As described earlier, land-based salmon farms also produce waste products, which can be handled as agricultural waste. But they also create large volumes of purge-water, that contain unknown chemicals and can overwhelm local streams. In addition, occasional die-offs of fish in tanks can create large quantities of organic waste that need to be disposed of immediately, and which may create problems for local waste management facilities.

Escapes. If nets are damaged, farmed fish might escape and interbreed with other wild fish. This can weaken wild stocks and alter their genetic diversity. This is of little concern in Chile and Norway, where wild salmon are absent, but is more of a concern in Atlantic Canada and Maine, where wild Atlantic salmon populations are struggling. In August 2024, over 10,000 fish escaped from a net pen in Ireland, and many were later found in streams with wild salmon. Although all Atlantic salmon are the same species, fish cultivated in Canada and Europe are derived from different genetic stocks which should not be mixed. Though interbreeding with wild Pacific salmon is less likely, salmon farming is prohibited in Alaska, but is allowed in British Columbia. Escapement can be limited mostly through proper siting of net pens and strict management of facilities.

Chemical inputs. The use of antibiotics in feed can promote development of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria, such as Vibrio (see Sustainable Seafood #5). Antifouling and pesticide compounds may also be used to maintain net and pen structures, and these can impact other marine life or contaminate fish flesh.

Use of fish protein. Salmon feed is primarily made from other types of fish protein such as menhaden, herring, or anchovies. Using a large quantity of small fish to feed larger fish is not an efficient use of the resource. For this reason, scientists have been trying to develop diets that are less dependent on fish protein. One possible replacement is taurine, a plant-derived amino acid that seems to work almost as well. Much of the fish protein has been replaced with vegetable oils, which increases the levels of omega-6 fatty acids in the fish.

Sea Lice. Farmed salmon also tend to be heavily infested with sea lice, a type of ectoparasitic copepod. Although they don’t affect humans, sea lice can damage, weaken, and kill fish, and can be transferred to wild salmon and other fish that swim nearby. Farmers may use pesticides to treat sea lice infestations. In Scotland, sea lice from salmon farms were blamed for the loss of a native population of sea trout (Salmo trutta). In addition to parasites, bacterial and viral diseases, such as nephrotic disease, can be transferred from farmed to wild salmon. For these reasons, net pen locations are highly scrutinized to ensure that they will not affect wild salmon runs.

Socio-economic. The widespread availability of farmed Atlantic salmon has turned what used to be a delicacy into a common daily food item. Its abundance has depressed prices for wild salmon, affecting the income of people and communities that fish for wild salmon, and their livelihoods. Net pen sites may conflict with other uses of the marine environment.

It’s Not All Bad News

Despite these potential problems, farmed salmon has a number of positive benefits.

Farmed salmon is considered to be highly sustainable by NOAA, the Marine Stewardship Council, and Seafood Watch.

It is available year-round at relatively low cost ($10-12 per pound).

It has introduced many more people to eating salmon, thus improving nutrition in general.

Farmed salmon have one of the highest feed conversion rates of any protein source. It takes 1.2 to 1.5 lbs of feed to produce one pound of salmon. In contrast, producing a pound of chicken, pork, or beef requires 2, 3-5, or 6-10 lbs of feed, respectively.

Farmed salmon tend to have higher amounts of omega-3 fatty acids, but also higher amounts of omega-6 fatty acids which are less beneficial.

Farmed salmon rarely have roundworm parasites, because they only consume pelleted food.

Despite a few observations of escaped Atlantic salmon in Pacific Northwest streams, there have not been any documented cases of Atlantic salmon breeding or establishing new runs. Furthermore, they cannot interbreed with Pacific salmon.

Salmo Summary

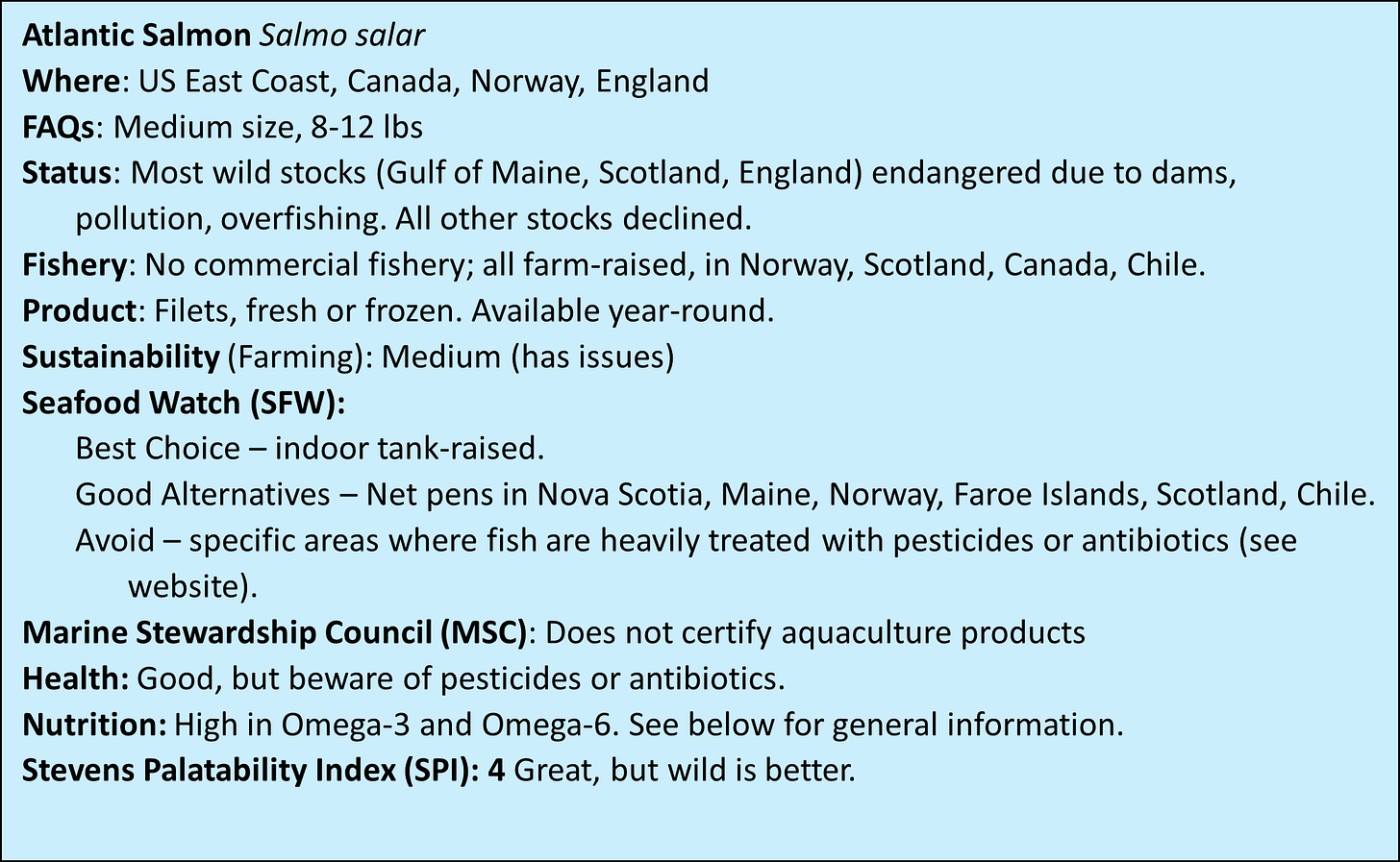

Information about farmed Atlantic salmon is summarized in the box below.

Salmon Nutrition. This information refers to Atlantic salmon but is generally applicable to other species. To create the table below, I compared about 60 seafood items to each other, plus other types of protein including beef (ground, pot roast, and top sirloin), chicken (whole, breast, wings), and pork (chops, loin). Serving size is 3 oz (about 85 g). Rather than provide numbers, I rank each nutrient in one of five levels within the range of compared items: Lowest (bottom 5%), Low (bottom 5-20%), Medium (25 to 75%), High (75-95%) and Highest (top 5%). Atlantic salmon has medium levels of most nutrients, but has the highest level of omega-3 fatty acids of any protein source (due to artificial feed), and the lowest cholesterol. It also has high levels of omega-6, which may be a concern.

Buying Salmon

The controversy about whether to eat wild Pacific or farmed Atlantic salmon has arguments and advocates on both sides. It is not my intention to adjudicate the issue here, but rather to encourage my readers to consume more seafood, especially salmon, and provide them with enough information to make informed choices. I have eaten both wild Pacific and farmed Atlantic salmon and enjoy them both. But given a choice, I would much rather buy wild Pacific salmon than farmed Atlantic salmon. Not only does it have better taste and nutritional profiles, but it also supports communities that depend on fishing. In restaurants, salmon may be listed without identifying it as wild or farmed, so I always ask. In grocery stores, anything labeled Atlantic salmon is farmed, and vice versa. It may be fresh, if it was shipped overnight from the source without freezing. You can usually distinguish farmed salmon from wild fish because the former have distinct white stripes in the flesh. These are caused both by higher fat content, and more collagen; wild fish spend more time swimming so have a higher ratio of muscle to fat or collagen content.

According to Seafood Watch, you should buy farmed Atlantic salmon from Maine, Denmark, and Faroe Islands, and sources that are certified by the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, but you should avoid buying farmed salmon from Canada, Chile, Norway, or Scotland (excluding Nova Scotia and Orkney Islands). Within those locations, however, there are different sources that may be on their list of Good Alternatives, so it pays to check their website.

Whether you choose to eat wild or farmed salmon, be assured that you are making a healthy, nutritious choice for yourself and your family. If environmental, economic, or social impacts are part of your consideration, so much the better. Making informed decisions improves the world for all of us.

Bon Apetit! Itadakimasu!

NOTE: Recipes for simple savory seafood are available on this site for paid subscribers.

This issue of Ecologist at Large is available to all readers. However, if you would like to support my work with a one-off contribution, click “Buy me a coffee” below.

I'm in Scotland and used to love eating salmon, but have given it up entirely due to the issues around farmed salmon. It's not always easy when eating out to find out where a salmon came from, so I just order something else. Maybe I'll try salmon again when I'm next in Orkney!

I have access to this farmed salmon: https://orakingsalmon.co.nz/. But you did not discuss it. Perhaps you aren’t familiar with it, but if you are, or will be, a little info or an opinion from you would be helpful.